NOTE FROM THE EDITOR

Dear readers, it’s my pleasure to share with you all this magnificent article that was posted by one of my good FB friends, Eduardo J. Bolaños, regarding the history of the Thanksgiving Holiday, which recently has been criticized in a negative way in an effort of give a bitter taste to a dinner time that unites families and friends in a peaceful dinner ceremony every year. The following article is a positive side of what the true Thanksgiving celebration is all about. Hope you had a wonderful and loving dinner ceremony, because I did, and for which I say thank you to those who invited me. – Marvin Ramírez

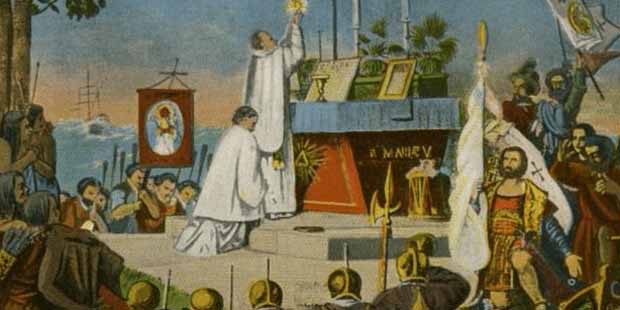

Before the arrival of the pilgrims to North American lands, in 2 Spanish expeditions in the years 1541 and 1598 to what is now the United States, Thanksgiving Masses were celebrated followed by a meal together with natives

THE FIRST (REAL) THANKSGIVING

The event of the first thanksgiving in this land is not that which was celebrated by the Pilgrims in 1621 as the vast majority of Americans have been taught. The real first thanksgiving to the one true God was celebrated eighty years before the Pilgrim’s feast! It occurred during the expedition of the Catholic Conquistador Francisco Vazquez de Coronado.

Beginning in 1539, Francisco Coronado organized a large expedition from Mexico, which included five Franciscan missionaries. He brought with him 336 soldiers and settlers, 100 native Mexican Christians, 552 horses, 600 mules, 5000 sheep, and 500 cows, pigs and goats. (This expedition marked the introduction of these animals into the south-western United States.) The expedition arrived in what is now Arizona and found Indian pueblos. After establishing a base in Arizona, Coronado headed east to establish a base-mission near present-day Albuquerque, New Mexico. When they crossed the river which is now called the Rio Grande, they named it Rio de Nuestro Señora (River of Our Lady). This is its original name as it appeared on the first maps of this region.

Though no supposed cities of gold were found in this region, Coronado continued to send out expeditions and send missionaries with them. That there were missionaries on every expedition should tell us that the search for supposed “golden cities” was not the primary reason for the explorations of Coronado. (The gold was needed to fund expeditions, and was not sought for personal gain.) Spreading the one true Faith among the pagan native Indians was of primary importance.

In April of 1541, Coronado, with a group of soldiers and some missionaries, left Albuquerque, New Mexico and headed north-east and crossed a section of northwest Texas (the Panhandle). In encountering some of the local Indians the missionaries found that the natives were immediately open to receiving the Gospel of Jesus Christ. After a few weeks of instruction, members of the Jumano Indian tribe converted and received Baptism. The expedition then arrived in Palo Duro Canyon where, on May 29, Father Juan Padilla, O.F.M., offered the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. (Father Padilla would eventually become the very first martyr of the Faith in America when he was martyred in 1542 in what is now Kansas.) A thanksgiving feast followed. It consisted of game that had earlier been caught. The feast was celebrated in thanksgiving to God for His many blessings and for the recent converts. This event is the first actual Thanksgiving Day celebrated in America by Christians.

There was another Thanksgiving celebration which also occurred years before the Pilgrims landed. In 1598, Catholic explorer Juan de Oñate led an expedition from Mexico City into New Mexico. The expedition included over 200 soldiers and colonists, the soldiers being headed by Captain Gaspar Pérez de Villagra. Many had their families with them. A number of Christian Indian converts with their families from Mexico were also in the party. With the group were several thousand head of livestock, including cows, horses, mules, sheep, goats, and pigs. Eighty three wagons carried provisions, ammunition, tools, plants, and seeds for wheat, oats, rye, onions, chili, peas, beans and different nuts.

On the expedition were two Franciscan priests and six Franciscan friar brothers. The party experienced many hardships. Soon after entering New Mexico, just across what is now called the Rio Grande River (originally named Rio de Nuestro Señora -River of Our Lady) near present-day El Paso, Texas, they were attacked by hostile Indians. A number of wagons and numerous head of livestock were lost. But no person from the expedition was killed, though a number Indians were killed in the attack.

After moving much farther north along the river, Juan de Oñate and the Franciscans erected a large cross and Oñate took possession of the land. He declared:

“I want to take possession of this land today, April 30, 1598, in honor of Our Lord Jesus Christ, on this the Day of the Ascension of Our Lord.”

Immediately afterward a High Mass was offered in thanksgiving. Then the entire group gathered for a banquet of thanksgiving to God for protecting them and for allowing them to arrive at the place after so many hardships along the way. The festive meal consisted of fish, game, fruits and vegetables. After this first thanksgiving banquet, the expedition headed further up along the river and by June had established the mission-town of San Juan (still populated to this day).

Though there was a thanksgiving feast celebrated in 1541, as we earlier saw, it was never commemorated afterwards. In contrast, for some years after the Thanksgiving Feast of 1598, a feast was celebrated by the Spanish and Christian Indians of New Mexico in thanks to the true God for bringing them through many hardships and for His blessings. Today this thanksgiving feast is commemorated every thirtieth day of April in San Juan, New Mexico.

It is only now that we can turn to the story of the Pilgrims and their thanksgiving. After a long and harsh winter, the Pilgrims received help from the friendly Wampanoag Indians in planting crops during the spring of 1621. They worked hard and in autumn had a very good harvest. In November of 1621 they invited the local Indians, who were still pagan and worshipped false gods, to feast with them to give thanks to God for the blessings of a successful harvest. The Catholic student of history should recognize that it is impossible to give thanks to the same God “together”, let alone the true God, when those involved believe in different gods. But this didn’t apparently bother anyone. (Recall, the Indians who took part in the true first thanksgiving were converts.) It should also be pointed out that the Pilgrim’s thanksgiving was more of a (successful) harvest celebration than a religious thanksgiving observance.

This event was not celebrated yearly by the Pilgrims, as many think and have been taught (they had done so only for a couple more years), nor by anyone in the original thirteen colonies for years. Though George Washington called for a day of Thanksgiving while he was President (only in response to the successful ratification of the Constitution), it was not celebrated as a yearly holiday feast until Abraham Lincoln established Thanksgiving Day as a holiday in November, 1863.

So now you know that the Pilgrims did not celebrated the first Thanksgiving in America. The first Thanksgiving feast was celebrated back in 1541, and the first annual feast in 1598 in New Mexico by Spanish-Catholic colonists and Indian converts to the Faith. They thanked the true God for bringing them safely through many troubles and dangers and that the seed of the Gospel of Christ was beginning to take root in this land. Because of the often anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic prejudice of English-Protestants (whose text books dominated the American educational system), generations of Americans have never learned these facts of our history.

-Adam S. Miller

(Taken from the soon-to-be published “Journey America: Pathways to the Present”, Marian Publications, Inc. This article was first published in a slightly abridged version in “From The Housetops,” Serial No.55, Fall, 2002)