Ten years ago, it was nearly destroyed. Today, its members are rebuilding through a new labor cooperative

by David Bacon

Mexico’s new President, Andres Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), probably the only head of state to give two press conferences a day and then post them online, is accustomed to having his statements cause headlines.

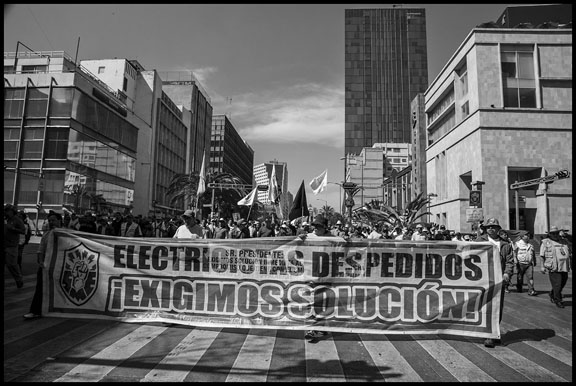

Last week it was a reporter’s question that caused a hot controversy, seemingly intended to drive a wedge between AMLO and one of his most important labor allies, the Sindicato Mexicano de Electricistas (Mexican Electrical Workers union, SME).

Reporter Rosa Elena Soto, of Acustik Noticias y La Neta Noticias, alleged corruption between Lopez Obrador’s predecessor and the union, over contracts for operating the huge Necaxa hydroelectric power station. “Many of these contracts have indications that they were plagued by corruption,” she charged.

In his response, AMLO called the union “possibly the most democratic union in Mexico’s history, until they viciously destroyed it in the neoliberal period.” Noting that its 44,000 members had been fired in 2009, he called for a solution to the conflict. Any corruption, he emphasized, wasn’t attributable to workers but to companies that took advantage of the situation. But López Obrador also called for consulting the discredited former leaders of the union, who had accepted government’s payoffs after the firings.

This response provoked outrage from the union’s leaders. SME General Secretary Martín Esparza replied: “We walked miles and miles in demonstrations, faced with dignity those who fired the workers. We did not sell out, even as our families suffered, and we didn’t just sit back with our arms folded and wait for answers. In fact, we proposed viable and novel solutions.”

That solution is a cooperative that has taken over many of the facilities where SME members formerly worked, including the Necaxa power station in the reporter’s question. This “novel solution” represents the union’s hope of putting back to work the thousands of electrical workers thrown into the street a decade ago.

When López Obrador carefully noted the union’s reputation, he was acknowledging the importance of its 100-year history on the Mexican left. The Mexican Electrical Workers Union, the oldest democratic union in Mexico, was founded in 1914 when the armies of Emiliano Zapata took Mexico City. Almost a century later, in 2009, the Felipe Calderón administration attempted to destroy the union and the nationalized company that employed its members. But thousands of the SME’s members refused to give up their union. Instead, they spent the next eight years en resistencia (in resistance).

This willingness to fight for principled labor policies is not only crucial to the country’s political left but has an impact across the border as well. Today, electrical workers in the U.S. work on an energy grid increasingly integrated with Mexico’s. To avoid the whipsawing and job competition familiar in industries like auto, U.S. unions will need Mexican partners with the kind of class-oriented unionism the SME has championed. That class-based unionism has a long history. In its new cooperative, that history is not only still alive, but has been adapted to the realities of an integrated economy dominated by pro-corporate reforms.

The origins of the SME’s class-based unionism

In 1898, the Compania Luz y Fuerza del Centro (the Power and Light Company of Central Mexico, LyF) was founded in Canada, and granted a concession by President Porfirio Díaz to generate, transmit, distribute, and sell electricity in central Mexico. In the middle of the Mexican Revolution, LyF workers organized the SME primarily because Mexican workers were paid much less than those working for the company from Canada and the United States.

In 1916, the SME organized Mexico’s first general strike. Union leaders were imprisoned and condemned to death, but their lives were ultimately spared after huge demonstrations. In 1936, the SME went on strike against the U.S., British, and Canadian owners of Luz y Fuerza. Mexico City went without electricity for ninety days, except for emergency medical services. The strike was successful and led to the negotiation of one of the most important labor contracts in Latin America. This contract preserved SME’s independence from the government, unlike other Mexican unions, and made it an important organization on the Mexican left.

In 1937, Amendment 27 of the Mexican Constitution made the oil and electrical industries the property of the state. Then, in 1949, the Comisión Federal de la Electricidad (Federal Electricity Commission, CFE) was established to provide power to all of Mexico-except for the area served by LyF. Nevertheless, private companies like Luz y Fuerza continued to operate under government concessions.

In 1960, the SME began to push for the nationalization of electrical power. The Mexican government subsequently purchased 90 percent of LyF shares, making it a state-owned and operated company. Then-President Adolfo López Mateos added a paragraph to Article 27 determining that the Mexican government has the exclusive right to provide electricity to the country.

The Sindicato Único de Trabajadores de Electricidad de la República Mexicana (Sole Union of Mexican Electricity Workers, SUTERM), headed by Rafael Galván, was established in 1972 for CFE workers. Galván, however, was expelled from the union for opposing government policy. He then organized the Tendencia Democrática del SUTERM, (Democratic Tendency of SUTERM), whose leaders were all fired. The union consequently became a pillar of support for Mexico’s governing party, the PRI. Since then, the two unions have represented the two poles in Mexican labor: an independent democratic organization with left politics, and a bureaucratized union tied to the PRI and the government.

(This article has been shorten due to its length. Here’s the link to read the entire article: https://davidbaconrealitycheck.blogspot.com/2019/02/the-rebirth-of-mexicos-electrical_7.html).