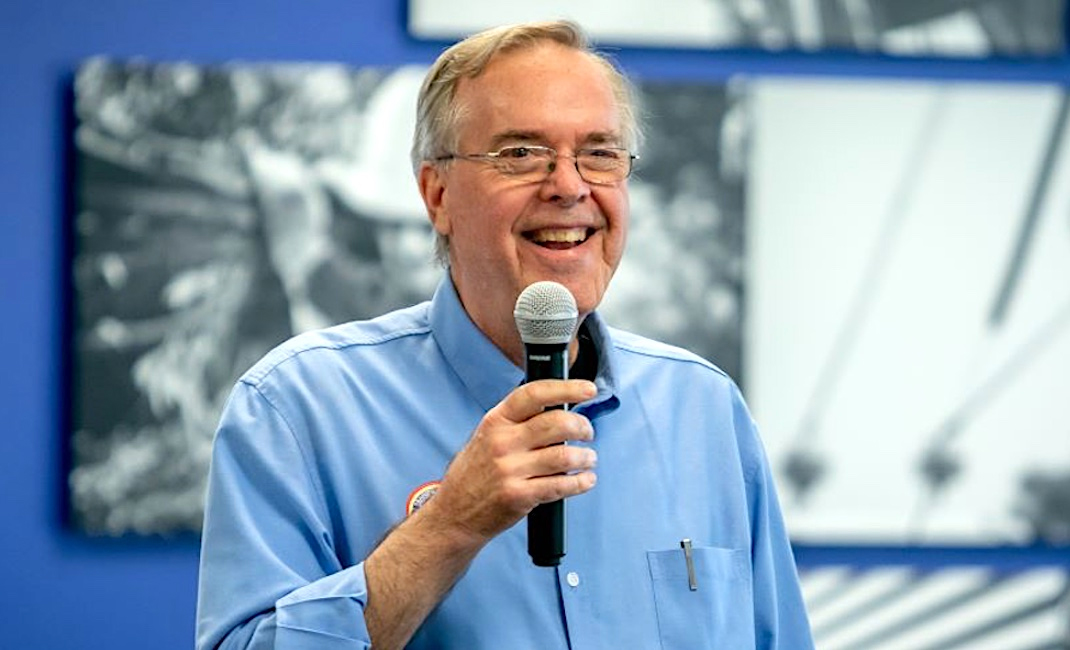

Fred Ross Jr., one of nation’s leading organizers, worked to improve conditions for farmworkers, attack causes of migration from Central America, and speed up the naturalization process

Fred Ross Jr. always wanted to be known simply as an organizer.

Beginning with his organizing work as a young man in the fields of California alongside César Chávez, he inspired countless people to achieve social change for more than half a century in the workplace and in communities across the United States.

Ross died of cancer on November 20 at the age of 75.

Dolores Huerta, a co-founder with Chávez of the United Farm Workers, said there were two words that describe Ross: humble and noble. “He was always so positive about everything,” said Huerta, now 92. “We had a lot of turmoil in the farmworker movement, but Fred always managed to stay above it. He remained a statesman.”

Arnulfo De La Cruz, executive vice president of SEIU Local 2015, recalled working with Ross two decades ago at the Providence St. Joseph’s Hospital in Burbank, part of the third largest nonprofit hospital chain in the West.

“I learned so much from Fred, especially how important it was to engage the entire community to support these workers, the faith community, labor, celebrities,” he said. “He felt as comfortable in Spanish as in English and the workers really took a deep liking to him especially as they further understood his family’s long legacy of fighting for working people.”

Ross followed in the footsteps of his father, Fred Ross Sr., another legendary organizer who had a profound impact on Chávez. “He discovered me, he inspired me,” Chávez said about Ross Sr., who hired and trained him as an organizer at the age of 25 in San Jose before he founded the United Farm Workers with Huerta. “He thought I had what it took to be an organizer. He gave me a chance, and that led to a lot of things.”

Ross Jr.s’ brilliance was to take what he learned from Chávez and his father, combine those lessons with field campaigns of local volunteers and a smart use of the media, and put pressure on employers, state governments and Congress on a range of social justice causes.

Ross began his work as a full-time organizer at age 23 with the farmworkers during the giant 1970 Salinas lettuce strike. One notable contribution was organizing a 110-mile march against Gallo wines, from Union Square in San Francisco to Gallo headquarters, where at least 10,000 farm workers and supporters filled the streets of Modesto.

A motive for the Gallo march was to pressure Gov. Jerry Brown to sign the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, enacted in June 1975. It was the first law of its kind establishing the right of farm workers to organize, vote in union elections, and bargain with their employers.

Ross employed house meetings as a central tactic throughout his career. That was the hallmark of Ross’ approach to organizing: building one-on-one relationships to, in his words, exercise “collective power.”

Arturo Rodriguez, who succeeded Chávez as president of the UFW, and served in that role for 25 years, said Ross “truly embodied Si Se Puede.” He said Ross’ belief in house meetings “throughout all these decades has been truly amazing and gave me faith to continue the house meeting process as our basic way of organizing.”

In the 1980s, Ross led Neighbor to Neighbor which initially focused on the plight of refugees from Central America but grew into a much larger effort to confront U.S. policies in the region that contributed to people fleeing their countries.

After putting pressure on Congress to end U.S. aid to the Contras, the rebel group fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua, Neighbor to Neighbor launched a boycott of Salvadoran coffee to pressure the government to withdraw its support of death squads. As a result of picket lines set up by Neighbor to Neighbor, longshoremen refused to unload coffee cargoes up and down the West Coast, including in Long Beach.

After California voters approved Proposition 187 in 1994 promoted by Gov. Pete Wilson, Ross helped launch the Active Citizenship Campaign in Los Angeles which successfully put pressure on the Immigration and Naturalization Service to speed up the application process for naturalization to six months.

“We not only played a tangible role helping thousands become citizens, but, more importantly, to become a lot more engaged in the whole political process,” recalled Ross shortly before he died. “That was a real breakthrough in continuing to build Latino voting power in California.”

During the last year of his life, Ross had devoted himself to producing a documentary film about his father’s legacy. The film, expected to be released in 2023, seeks to inspire others to organize by highlighting the impact of grassroots organizing on long term change.

“As with his father, Fred Jr.’s labors were never about himself,” the United Farm Workers said in a tribute. “He was always about empowering others to believe they were responsible for the progress they won. Fred Jr.’s nature was ceaselessly positive; he always thought things could be done.

Ross is survived by his wife, Margo Feinberg; his children, Charley and Helen Ross; brother, Robert Ross; and sister, Julia Ross. In his memory, the family asks that contributions be made to the Fred Ross Sr. documentary project via fredrossproject.org. Condolences and memories sent to FredrossMemories@gmail.com will be shared with his family.