[Author]by Barry Krisberg

Commentary[/Author]

An earlier version of this column first appeared in The Conversation

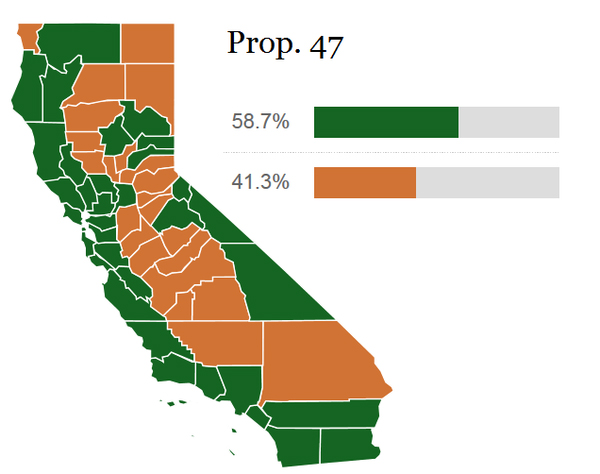

This week, Californians resoundingly approved a ballot initiative—Proposition 47, the Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Act—that will not only have a major impact on California’s prison population, but have significant resonance across the U.S.

The initiative, which passed with 58.5 percent of the vote, changes many crimes from felonies, which generally require prison terms, to misdemeanors that usually carry penalties of probation, fines or very short jail time. Most instances of drug possession and property crime under $950 are no longer felonies. Current prisoners who were charged with these crimes can now petition to have their sentences reduced.

A modest estimate is that Proposition 47 will reduce the California prison population by 10,000 inmates although there will still be about 125,000 prisoners in the state’s prison system after the reforms take hold. It will save California taxpayers hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars and use those savings to support education, mental health and substance abuse counseling, and help for victims of crime.

Proposition 47 is one of the most far reaching pieces of criminal justice reform anywhere in the nation. The initiative may be the beginning of a national trend.

The Golden State has a long tradition of deciding important social policy questions via the general electoral process.

In the 1970s and 1980s advocates of tougher crime laws used ballot measures to break through the perceived dominance of San Francisco Bay Area liberals in the state legislature.

Almost every election year there were new initiatives that created mandatory prison terms for a range of offenses. The most well-known of these measures was 184, popularly known as “Three Strikes and You’re Out.” This measure was approved by 71 percent of voters in the 1994 election. It mandated a life sentence for almost any crime, no matter how minor?

As a result of these voter-approved laws, California’s prison population soared—increasing by 900 percent between 1980 and 1995. But this came at an added cost of almost $9 billion annually. The increase in the number of prisoners led to the construction of almost two dozen new prisons. Even these new prisons could not avoid severe crowding conditions.

Money played a huge role in determining the outcome of these measures at the ballot box.

The television and radio spots often contained flagrant misrepresentations to sway voters to support these “tough on crime. For example, in 2004 reformers managed to get Proposition 66 on the ballot, a measure that would require that the “third strike” putting someone behind bars for life be a violent crime. In response, then Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger saturated television with ads claiming that Proposition 66 would release 26,000 dangerous criminals and rapists.

The TV spots showed pictures of notorious criminals who were already sentenced to death and would not be affected by Prop 66. The opponents of Prop 66 poured over $ 3 million into the print and electronic campaign. Public opinion turned negative on Prop 66 in the final days before election and the measure was ultimately defeated.

Earlier in 1996, Californians voted to decriminalize marijuana for medical use; and in 2012 another ballot measure, “Changes in the ‘Three Strikes’ Law” reduced the harshest penalties introduced by Proposition 184.

Over the course of these campaigns, progressive reformers have become better at raising money and competing in California’s vast media market. However, initiatives increasing penalties for sex offenders and efforts to increase the time served by life sentenced inmates such as Marsy’s Law are still very popular with the public.

Which brings us to Prop 47.

The Yes campaign brought together a wide assortment of interest groups that had not agreed about criminal justice policy in the past. Recent campaigns to challenge capital punishment and to reform the three-strike law helped forge a broad coalition of some victims’ rights groups along with powerful allies such as organized labor, the California Teachers Association, the California Nurses Association and state Democratic Party.

The most visible advocates for Prop 47 were San Francisco district attorney George Gascón, Santa Clara district attorney Jeff Rosen and former San Diego Police Chief William Landsdowne. These respected law enforcement officials viewed California’s mass incarceration policies as fiscally unsustainable and harmful to low income communities.

Even prominent national conservative figures like Newt Gingrich and Rand Paul announced their support for Proposition 47, arguing that current sentencing laws waste taxpayers’ dollars and do not curtail drug use. They prefer a focus on locking up violent offenders.

While Senator Dianne Feinstein spoke out against Prop 47, many other state leaders such as Gov. Jerry Brown and Attorney General Kamala Harris remained neutral. One traditionally powerful lobby group, the Corrections Peace Officers Association took no position on Prop 47.

It is significant that virtually all the past California governors and attorneys general almost always sided with the tough-on-crime position in ballot initiatives. In the case of Prop 47, their silence was deafening and hampered fundraising for the No camp.

The advocates of Prop 47 raised over $10 million to run their campaign. In contrast, their opponents (who were mostly police chiefs and a few district attorneys) raised only about $1 million. The opponents of Prop 47 got virtually no traction among the editorial boards of the largest news outlets.

Since 1994, California has suffered a severe economic recession and government services at every level were slashed. Tuition at state colleges and universities skyrocketed, and some cities have been on the edge of bankruptcy. Many cities and towns have been forced to cut basic services including police and fire departments. Recent tax increases have helped but they are temporary.

But it’s not just about the money. Public confidence in the state’s prison policies has eroded.

Even the US Supreme Court declared the prisons so crowded and inhumane that it ordered the release some inmates. This dramatic court judgment led Californians to reconsider who should go to prison. Harsh criminal justice laws have been on the books long enough for Californians to be able to weigh the cost and benefit of these measures. The well-publicized failure and financial drain of the so-called “War on Drugs” has created has an environment in which voters are seeking new ideas.

More generally, the popularity of Prop 47 resonates with a growing distrust of government overreach into citizens’ lives and a preference for decision making that is closer to where people live. The demographics of the voting public which is younger, more ethnically diverse, and more highly educated than ever before is also favorable towards more progressive social policies.

If California helped lead the national charge in favor of more tough on crime laws, the state could lead the charge in the opposite direction.

California has traditionally been ahead of national developments, but a good predictor of future political trends. Since California is the largest state in the country, if Prop 47 passes other states may well follow suit. As California goes, so goes the nation.

Barry Krisberg is a Senior Fellow at the University of California Berkeley Law School.