For decades, the specter of Andrés Manuel López Obrador has haunted Mexico’s ruling elites. His triumph on Sunday could change the country’s domestic, regional, and international outlook, says Dan Steinbock

by Dan Steinbock

Political analysis

International media touted the neoliberal reforms of President Enrique Peña Nieto for the past year or two. However, when the “reform” narrative proved hollow, Nieto’s approval rating plunged from almost 50 to barely 10 percent. So the establishment narrative changed: it shifted to a flawed portrayal of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as a Mexican Hugo Chávez who endangers Mexico’s future.

Perhaps that’s why before his landslide election victory as president on Sunday The Economist called Obrador “Mexico’s answer to Donald Trump” whose “nationalist populism” offers “many reasons to worry about Mexico’s most likely next president.” Similarly, U.S.-based economic hit men and political risk groups, including Ian Bremmer’s Eurasia Group, framed Obrador’s popular front as a “significant market risk.”

With few variations, the same narrative was replicated in establishment media. The Washington Post, The New York Times, Time, Newsweek and The Financial Times warned of a “firebrand leftist” whose biography is “replete with danger signals.”

What these ideologically-driven reports didn’t say is that Obrador is neither an overnight phenomenon nor Trump-induced collateral damage. In reality, Obrador’s movement is a belated triumph for Mexico’s popular will after decades of electoral fraud.

In the past six years, Nieto’s administration has sold Mexico’s public assets to foreign bidders and opened financial markets to speculation, while loyally accommodating Washington’s policies. At the same time, corruption, crime, narco-violence and rising murder rates have soared. While neoliberal elites portray the past decade as that of rising competitiveness, market realities prove otherwise. Mexico’s real GDP growth has fallen significantly behind its BRIC potential during the years of Felipe Calderon (2006-12) and Nieto (2012-18).

But change may be at the door. Obrador will be inaugurated in December. His coalition “Juntos Haremos Historia” (Together We’ll Make History) rests on popular will, not on the needs of the oligarchic economic and political elite, or what Obrador calls the “power mafia.”

He is pushing for the rejuvenation of the agricultural sector. In particular, he would like to develop the agricultural economy of southern Mexico, which has been hurt by cheap (and tacitly subsidized) U.S. food imports. In contrast to Nieto’s “energy reform” – which ended state-owned Pemex’s monopoly in the oil industry and brought foreign investors to Mexican energy markets – Obrador wants a popular referendum on the energy sector, knowing well that many Mexicans oppose or are highly skeptical of the sale of national assets to foreign speculators.

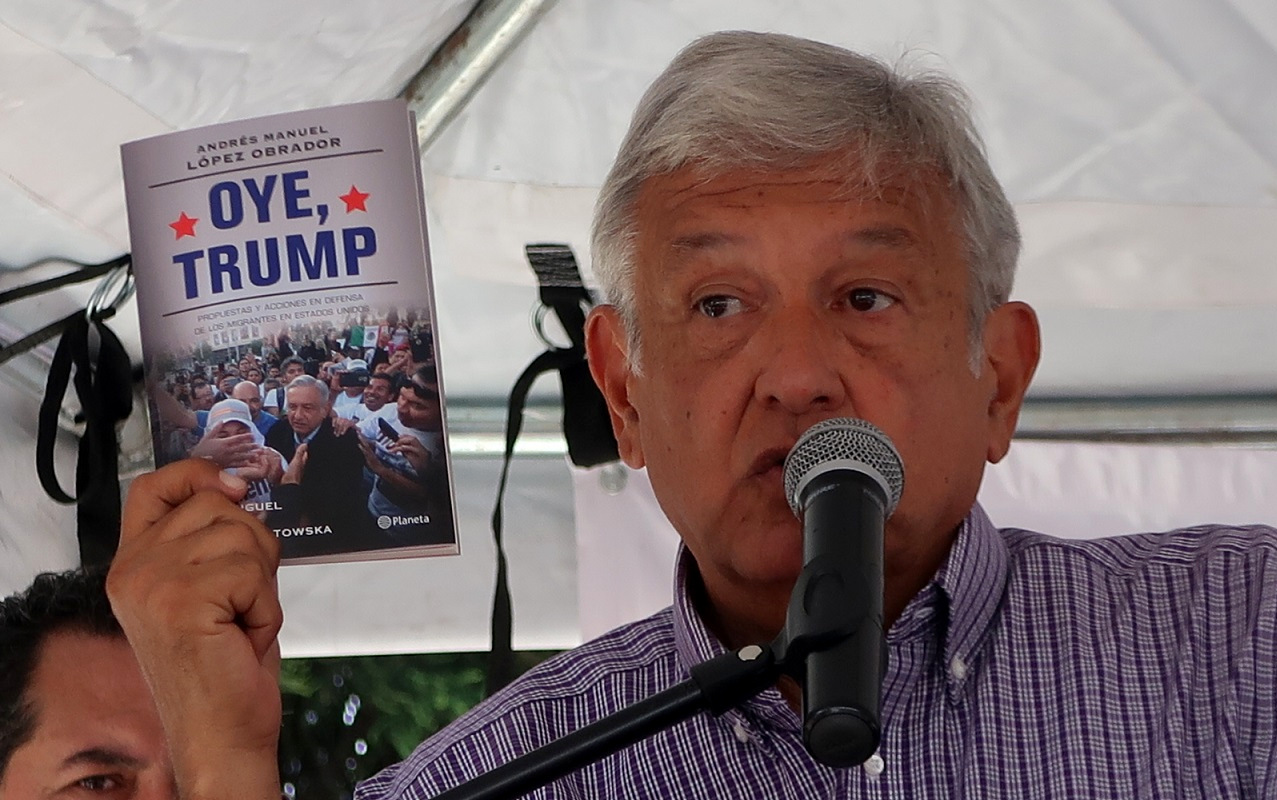

Book on Trump

After Trump’s inauguration, Obrador published a best-selling book called Oye, Trump, in which he takes a critical look at the American “Caligura on Twitter.” While he is politically too shrewd to challenge Trump head on, he is not an appeaser like Nieto. And unlike Nieto, Obrador also had no hurry to conclude the Trump talks about the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Through the election campaign, he supported the delay of renegotiation of NAFTA until the elections, so he can have a say in the final outcome.

Obrador seeks increased spending for welfare, which he argues should be a central political objective in a large emerging economy. He is also a strong proponent of cutting the salaries of the political elite to avoid penalizing ordinary Mexicans. He is willing to walk the talk: he has cut his own public-service salary, several times.

Delfina Gómez, an Obrador ally running for Mexico’s senate, told The Guardian: “He finds it shameful that someone might be flaunting their wealth whilst others are dying of hunger.”

Instead of pushing elite educational objectives, Obrador seeks educational reforms through universal access to public colleges and proposes increases in financial aid to students and the elderly.

Having been mayor of Mexico City, he knows only too well how the ruling elite operates in the imperial metropolis. As a result, he is strongly in favor of the decentralization of the executive cabinet by moving secretaries from the capital to the states to be closer to the people that they should serve, and further from the lobbies they tend to collude with.

In contrast to ‘law and order’ candidates that in the past have colluded with the drug kingpins, he wants to restore genuine law and order and thus peace and stability, in order to focus on economic development. He might even seek to negotiate an amnesty for the key narco criminals.

Obrador’s platform reflects popular will. That’s why it has been marginalized by the oligarchic elites for decades – even with electoral fraud.

Decades of Electoral Fraud

Born in 1953, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, often abbreviated as AMLO, is everything but a new force or overnight phenomenon in Mexican politics. Starting his career in 1976 in the then-dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in Tabasco, on the Gulf of Mexico, he soon became the party’s state leader. In this capacity, Obrador saw intimately how PRI’s longstanding political monopoly began to crumble as domestic elites and foreign interests paved the way to Carlos Salinas’s presidency (1988-94).

Following a highly controversial electoral process and reported electoral fraud, Salinas, who had been groomed at elite U.S. universities, subjected Mexico to neoliberal reforms, which led to years of an economic rollercoaster climaxing with NAFTA. A series of other presidents took office—from Ernesto Zedillo and Vincente Fox to Calderón and Nieto – all promising economic reforms, a war against drugs and a better future. Yet, each, despite different parties, shared a common denominator: neoliberal economic policies, which were predicated on the continued embrace of NAFTA, the expansion of cartels, and jumping on the bandwagon of U.S. policies.

Dr. Dan Steinbock is an internationally recognized strategist of the multipolar world and the founder of Difference Group. He has served at the India, China and America Institute (US), the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore).

Note: This article was cut to fit space. To read the complete piece, please visit us online at: elreporteroSF.com