The names Rivera, Kahlo, Siqueiros and Orozco still dominate the imagination when it comes to Mexican art, but did you know that from the 1920s to the 1950s, Mexico’s muralism movement has so much prestige internationally that it displaced Europe for a time?

Such would have been unthinkable during the preceding Mexican Revolution, but afterwards, several factors came together to make Mexico an irresistible draw for young, idealistic foreign artists.

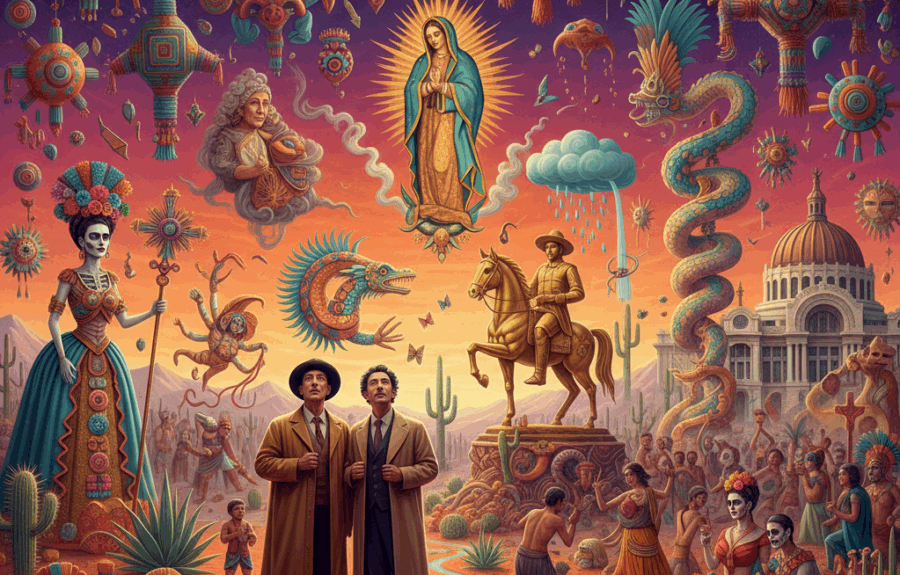

Mexico was undergoing momentous changes in its identity, with a post-Revolution government needing to establish legitimacy and its ideology among a populace that was still mostly illiterate. Without mass media, murals were one way to promote Mexico as a blend of indigenous and European, with a healthy dose of socialism thrown in.

Government mural commissions became prestigious, and many sympathetic artists benefited, but none more so than the “big three”: Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco.

Muralism was highly nationalistic, but aspects of it appealed abroad. The legacy of colonialism was starting to be debated, including the (re)integration of native identities. While documenting the violence of the Revolution, foreign photographers also captured scenes of Mexico’s many traditional communities.

These communities appealed to many weary of Western industrialization. Last, but not least, was the socialism/communism of many of Mexico’s artists as part of a global movement.

One other important factor would be war and other strife in Europe, making Paris too dangerous for budding artists.

Early artists who came and explored Mexico’s artistic possibilities included Everett Gee Jackson and Lowell Houser in 1923, who would eventually make their way to the Lake Chapala area.

For the next three decades, it is not known how many foreign artists came, but many are referred to in Mexican history as “assistants” — something of a misnomer. Many were young and looking to start careers by piggybacking on Mexico’s prestige, but few worked as true assistants to established Mexican artists.

One reason was that Mexican artists did not see value in the participation of outsiders. This was particularly true of Siqueiros and Orozco; Rivera was more open to foreigners.

Despite that negativity, there are a number of notable non-Mexican muralists. The first is Frenchman Jean Charlot who painted “The Conquest of Tenochtitlan” (1922) and “Dance of the Ribbons,” the last of which was destroyed in 1925 by none other than Rivera, and Charlot left Mexico to have a successful career in the States.

Other names include Ione Robinson, Pablo O’Higgins, Rina Lazo, Marion and Grace Greenwood, Howard Cook, Philip Guston, Reuben Kadish, Ryah Ludins and Isamu Noguchi. Although they shared high hopes upon entering Mexico, their experiences varied quite a bit from the idyllic to absolute disillusionment.

Robinson was the closest to an “assistant,” working on projects that Rivera assigned her — at least until Kahlo got jealous and sent the young woman packing.

What most of these artists did was to find or create projects outside of prestigious governmental commissions inside of Mexico City.

Marion Greenwood went to Taxco and convinced the Hotel Taxqueño to let her paint “Taxco Market” (1933), followed by “This Landscape and Economy of Michoacán” at the University of San Nicolás Hidalgo in Morelia with her sister Grace. Neither were paid apart from expenses, but the works opened doors back in the U.S.

Similarly, Howard Cook would paint “Taxco Fiesta” at the same hotel just after Greenwood, then paint murals in U.S. post offices.

Most never considered staying in Mexico, but are interesting exceptions: Pablo O’Higgins is a classic case of “going native,” deciding everything about Mexico was superior to his native U.S. He would have a decades-long career painting murals and would have a hand in setting up foreign artists with projects, culminating in the massive project at Mexico City’s Abelardo L. Rodríguez Market in the 1950s.

Rina Lazo came from Guatemala on a scholarship in the 1930s. Both her personal and professional lives were strongly linked to Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, starting out as an assistant then moving on to create important murals of her own. Her husband was one of “Los Fridos” (students of Frida Kahlo). Lucky for me, I met her shortly before her death in 2019, and her devotion to Diego and Frida remained unshaken.

But not everyone was thrilled with what they found here. In 1934, Philip Guston and Reuban Kadish came to Mexico to paint “The Struggle Against War and Fascism” in Michoacan. But they quickly became disillusioned.

According to Guston, “The much heralded Mexican renaissance is very much a bag of hot air. I can’t explain to you my disappointment in [Rivera]. His work is absolutely a horrible mess. … Charlot’s fresco … is, of course, the best thing here.”

Both Guston and Kadish left Mexico behind for other artistic trends and did not talk much about their experience in Mexico.

Classic muralism’s last hurrah was the Abelardo L. Rodriguez Market project. Rivera was officially in charge and had significant influence in how the project developed, but artist recruitment and supervision fell onto Pablo O’Higgins. Here, he reunited the Greenwood sisters, along with Russian artist Ryah Ludins, Japan’s Isamu Noguchi and others, each with wall space of their own.

One other important foreigner-linked project is a never-completed mural by David Siqueiros in San Miguel Allende from the early 1950s. Siqueiros was hired by the local art school to do the work with students, but the deal went sour. The mural remains an important tourist attraction in the city.

Those mentioned here are by no means a full list of the foreign artists who came to Mexico at muralism’s height, but they are part of the reason why muralism remains relevant here, even if no longer avant-garde.