NOTE FROM THE EDITOR:

Due to the lack of space, we are publishing this article without the second part – an interview to Rosario Ventura, from Oaxaca, Mexico, who in her own words describes her personal history that led her to migrate yearly from California to Washington, and then become a striker.

by David Bacon

Dollars and Sense

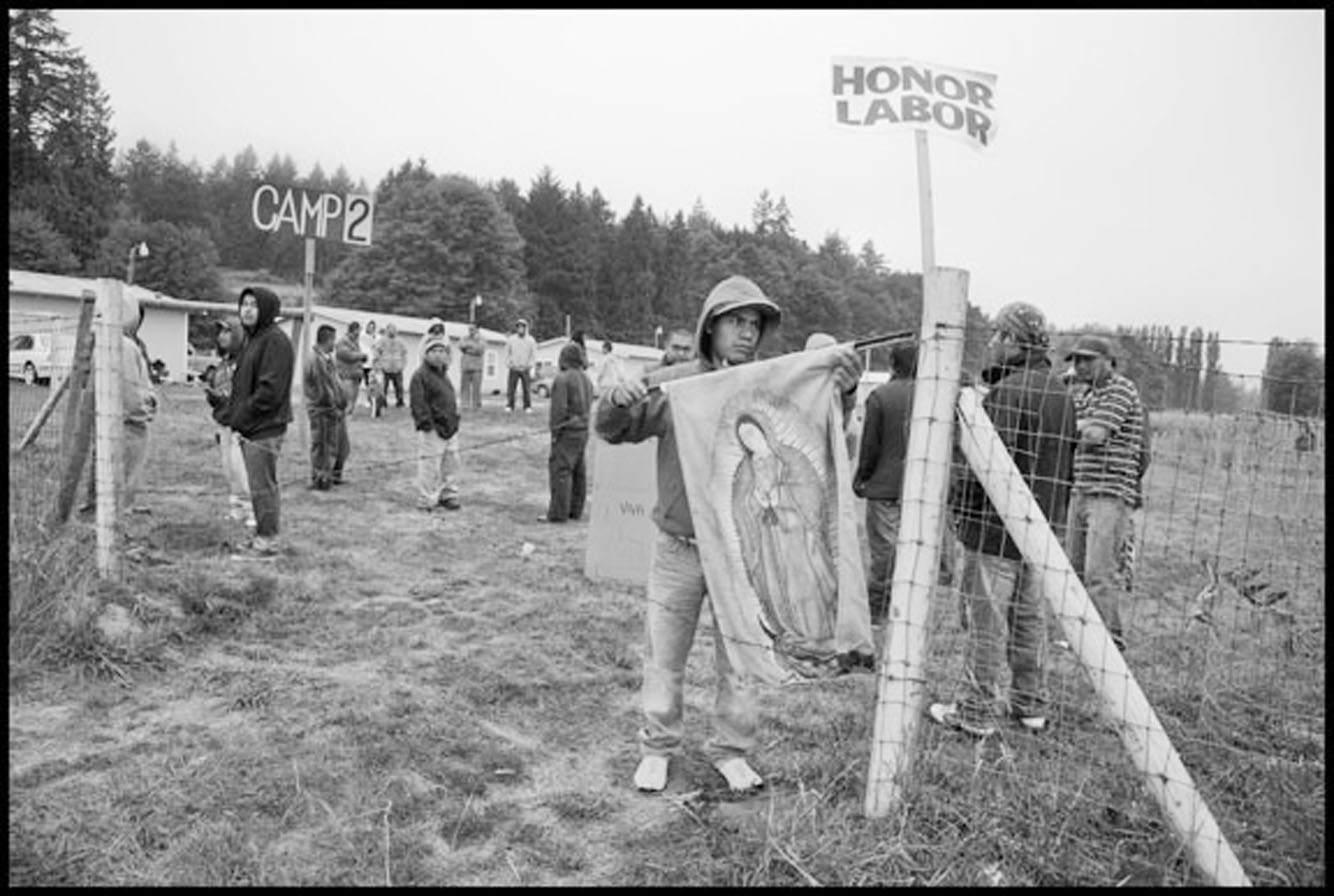

In 2013, Rosario Ventura and her husband Isidro Silva were strikers at Sakuma Brothers Farms in Burlington, Wash. In the course of three months over 250 workers walked out of the fields several times, as their anger grew over the wages and the conditions in the labor camp where they lived.

Every year the company hires 7-800 people to pick strawberries, blueberries and blackberries. During World War II the Sakumas were interned because of their Japanese ancestry, and would have lost their land, as many Japanese farmers did, had it not been held in trust for them by another local rancher until the war ended. Today the business has grown far beyond its immigrant roots, and is one of the largest berry growers in Washington, where berries are big business. It has annual sales of $6.1 million, and big corporate customers like Haagen Dazs ice cream. It owns a retail outlet, a freezer and processing plant, and a chain of nurseries in California that grow rootstock.

By contrast, Sakuma workers have very few resources. Some are local workers, but over half are migrants from California, like Ventura and her family. Both the local workers and the California migrants are immigrants, coming from indigenous towns in Oaxaca and southern Mexico where people speak languages like Mixteco and Triqui. While all farm workers in the U.S. are poorly paid, these new indigenous arrivals are at the bottom. One recent study in California found that tens of thousands of indigenous farm workers received less than minimum wage.

In 2013 Ventura and other angry workers formed an independent union, Familias Unidas por la Justicia-Families United for Justice. In fitful negotiations with the company, they discovered that Sakuma Farms had been certified to bring in 160 H-2A guest workers. The H2A program was established in 1986 to allow U.S. agricultural employers to hire workers in other countries, and bring them to the U.S. In this program, the company first must certify that it has tried to hire workers locally. If it can’t find workers at the wage set by the state employment department, and the department agrees that the company has offered the jobs, the grower can then hire workers outside the country.

The U.S. government provides visas that allow them to work only for this employer, and only for a set period of time, less than a year. Afterwards, they must return to their home country. If they’re fired or lose their job before the contract is over, they must leave right away. Growers must apply for the program each year. On hearing about the application, the striking workers felt that the company was trying to find a new workforce to replace them.

When the company was questioned about why it needed guest workers, it said it couldn’t find enough workers to pick its berries. But the farm was also unwilling to raise wages to attract more pickers. “If we [do], it unscales it for the other farmers,” said owner Ryan Sakuma in an interview. “We’re just robbing from the total [number of workers available]. And we couldn’t attract them without raising the price hugely to price other growers out. That would just create a price war.” He pegged his farm’s wages to the H-2A program: “Everyone at the company will get the H-2A wage for this work.”

“The H-2A program limits what’s possible for all workers,” says Rosalinda Guillén, director of Community2Community, an organization that helped the strikers. Community2Community, based in Bellingham, advocates for farm worker rights, especially those of women, in a sustainable food system. The following year Sakuma Farms applied for H-2A work visas for 438 workers, saying that the strikers weren’t available to work because they had all been fired. Under worker and community pressure, Sakuma withdrew the application when it seemed probable that the U.S. Department of Labor (USDoL) would not approve it. Sakuma has still not recognized the union, and many workers feel their jobs are still in danger.

A decade ago there were hardly any H-2A workers in Washington State. In 2013, the USDoL certified applications for 6,251 workers, a number that had doubled just since 2011. The irony is that one group of immigrant workers, recruited as guest workers, is being pitted against another group-the migrants who have been coming to work at the company for many years.