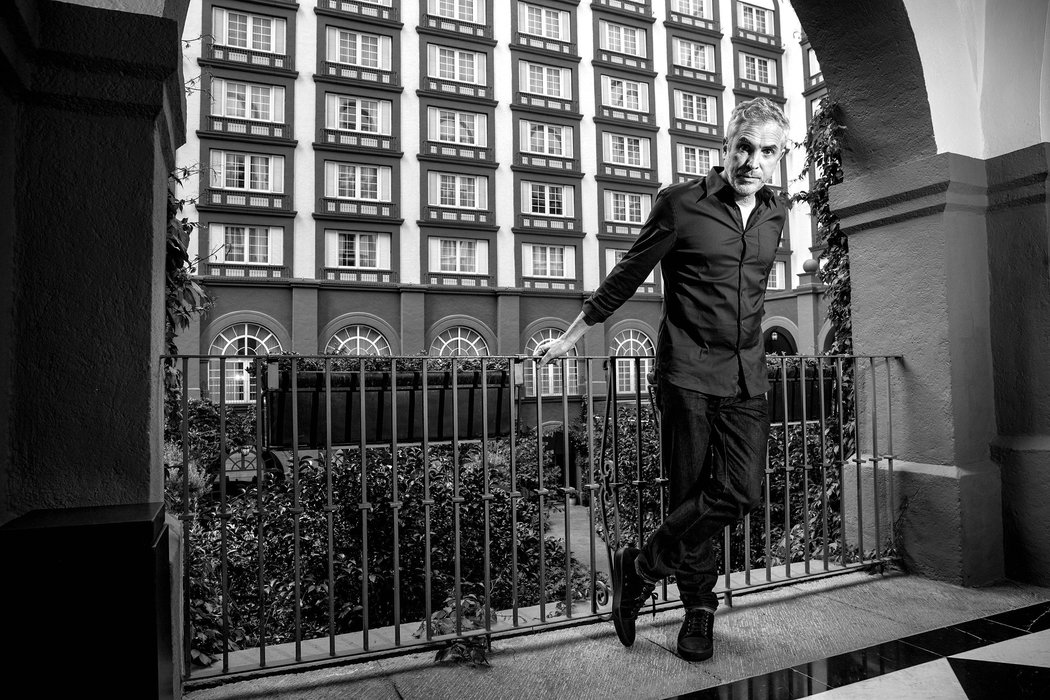

With a new film on Netflix this week, the iconoclastic auteur opens up about facing his insecurities in the latest edition of The Red Bulletin – a monthly magazine produced by Red Bull Media House.

by Marco Payán

The Mexican film director has no fear of the unknown. Upon the release of his new film, “Roma,” the Oscar winner shares how he overcame feelings of insecurity and why his curiosity to explore uncharted territory is what challenges him to unlock new levels of creative freedom.

Alfonso Cuarón does not like to repeat himself

Over the course of his nearly 30-year career, the acclaimed director has created eight distinctive universes, an octet of films not bound by genre or geography — from the enchanting fairy tale “A Little Princess” and the coming-of-age road trip “Y Tu Mamá También” to the apocalyptic nightmare of “Children of Men” and his Oscar-winning turn in space with “Gravity.” But despite all the obvious differences, Cuarón’s entire body of work is connected by a sense of exploration, one that pushes his creative boundaries, both technically and personally. In his follow-up to 2013’s “Gravity” — the box office smash starring Sandra Bullock and George Clooney — Cuarón decided to make “Roma,” a black-and-white film rooted in 1970s Mexico City featuring a largely unknown cast (available on Netflix December 14). It’s a deeply personal story for the 57-year-old, who has said that 90 percent of the scenes came from his memory. Set during a time of political unrest, the film is a snapshot of one middle-class family told through the perspective of their housekeeper. Although it is not another technical marvel set in space, “Roma” still posed challenges for Cuarón. But as he explains, without challenging yourself, there is no payoff. There are no discoveries unless you have the courage to explore the unknown.

The Red Bulletin: You’ve said in past interviews that you burned your bridges in Mexico. That’s obviously not something you’d recommend?

Alfonso Cuarón: It is so exhausting, and it’s not good for business. The way I produced my first film, “Sólo con Tu Pareja,” wasn’t looked upon terribly well. I had a lot of support from the Mexican government, but their investment was minor. I was adamant that they were not my bosses. The film was under my control and that didn’t seem to please everyone. I wanted to manage the movie the way I believed was best. I was aware that I would fall out of favor for any projects to come. So I ended up [taking the film to the] Toronto Film Festival, fully knowing what I had left behind, with the prospects of either going back or starting over. And then I began receiving offers from the United States.

How was your first experience working in the States?

I remember directing an episode of “Fallen Angels” for Showtime. I was full of insecurities and feeling numb. Besides, I was the only unknown director in the series. The other directors included Steven Soderbergh, Jonathan Kaplan, Phil Joanou — even Tom Cruise and Tom Hanks directed an episode. If Tom Hanks’s project needed a couple more days, those were taken away from me. I felt ignored. That’s why I’m so grateful to my actors, Alan Rickman and Laura Dern, because when they saw me paralyzed like that they told me, “Relax, we are here for you. We want you to direct us and we are going to do whatever you tell us to do.” At that point I finally began to let go. And then my episode, “Murder, Obliquely,” won all these awards. It was then and there that a friendship with Alan Rickman and Laura Dern was born.

Where did those insecurities come from?

When I first came to Hollywood, it wasn’t about being Mexican but about being from a Mexican generation so different from today’s Mexico. It used to be a closed-tight Mexico, oblivious to the world. It was a Mexico where looking for international impact was seen as a sign of arrogance. It was almost considered a lack of nationalism. I grew up in Mexico during the height of the PRI [Institutional Revolutionary Party], in the age of revolutionary nationalist ideology and closed markets, of repression and an enormous control over information, both incoming and outgoing. What movies were shown and what kind of music was played. Rock concerts were strictly forbidden. Then the first rock concert was the band Chicago at the Auditorio Nacional. There was so much repression that the moment it opened up a bit for a little concert, people destroyed the doors. That was our “being young” attitude. That was our outlet. When I came to the States in the early ’90s, I was still living with the ghost of that sick perception Mexico has of Hollywood — too romanticized and idealized.

How have your perceptions changed?

Those insecurities at the beginning of my career were not because of being Mexican but because there was an ideology. Now there’s a new generation that has no borders or limits. This is natural for them. I admire them because of that. They have no complex. From then on, my insecurities were no longer creative.

You’ve been open about your disappointment with “Great Expectations,” your second U.S.-produced film after “The Little Princess.” What did you learn from that process?

With “Great Expectations,” I was seduced by the machinery, and I had to pay the price. It was a movie I didn’t fully understand. I thought something I didn’t understand would work if I used visual tools. I was overcompensating. Once I became aware of that problem — that’s the reason I made “Y Tu Mamá También.” With that project I developed a whole new point of view about filming. Even in “Great Expectations” I wanted to do something technically polished and clean. El Chivo [cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki] and I came from a cine Mexicano that wasn’t crafted with excellence. Except for a couple of directors, the cinematographic language was poor. Photography wasn’t done properly. We were trying to shake things up. It wasn’t until “Y Tu Mamá También” that technique ceased to matter — what really mattered was the subject and the concept. The special thing about “Roma” is that it’s the first film where I feel completely liberated, completely free of insecurities. I had the certainty I didn’t know how to make it but I had no fear to explore. To give in completely to the idea I had of the movie I wanted to make.

You didn’t know how you were going to make the film, but you proceeded anyway?

I am inclined to try to imagine how I’d film a certain movie, but if I know how to do it I lose interest. If I know how to do it I get bored with the idea. More than the challenge, it’s curiosity for the unknown that drives me. It’s curiosity for knowing I have a perspective about the film I want to make, but I have no idea about how to do it. The process itself doesn’t let me lower my guard. That’s why I believe all the movies I have made are so different from each other.

Where does that sense of exploration come from?

It might have to do with being a film buff since my childhood and watching how big the universe known as cinema is, and admiring how the language of movies developed, from silent film, the birth of the cinema, to these days. There’s something that overwhelms me from time to time — the idea of not exploring languages. Or of not pushing the limits of certain languages. I believe that’s what attracts me the most.

Your latest film, “Roma,” was a rather large production, even though the story revolves around a more intimate family drama. Would you be interested in making a “simpler” movie?

More than just the plot, I see it as the whole cinematic experience. Indeed, it was what the cinematic experience demanded. Every time I begin a new project I say, “This is a simple film; this one’s going to be simple. I’ll make it fast and that’s it.” My producer always tells me that. For “Gravity,” I said to Chivo, “Let’s make a film the fast and easy way. This is about a woman in space — so we’ll just film her against black backgrounds and that’s it. [Laughs.] Some visual effects and we’re done.” When I began talking to my producer about “Roma,” I insisted, “This is a smaller, more intimate film.” And it’s no lie. But whenever I begin to prepare [for a project], reality starts to show up.

It’s also a chance to watch a big production that really reflects Mexico City.

I would expect that the production doesn’t become the focus, though. The universe within the movie should be the focus. The whole idea is to confront you with a universe.

You’ve been wanting to make a film based on El Halconazo — a massacre of student demonstrators in Mexico City in 1971 — for quite some time, correct?

Yes, I was planning on doing this movie 12 years ago. But because life happens and there are things you can’t control, I wasn’t able to make it back then. I believe it was for the best, though, because I was not mature enough for it. But a lot of the content in “Roma” was already in that early version.

I’m aware of your love for the 1976 Felipe Cazals film, “Canoa,” which also addresses the student protests during that period.

That was shot not long after [the Tlatelolco student massacre in] ’68, when it was off-limits to talk about that. What Felipe did was talk about that subject obliquely, indirectly. He also talked about the whole Mexican sociopolitical context.

Is Roma indebted to “Canoa” at all?

For “Roma,” I tried consciously to avoid influences and references. It was hard, because I have always thought about other movies while filming. I even watch some movies as inspiration, even if they are completely different, as long as I find an emotional connection or a shared language with whatever I am doing. In “Roma,” I didn’t want any of these influences, because I needed to be faithful and pure to the idea of re-creating memories. I remember whistling a melody while framing a shot. I noticed it was a Bach tune that was used in a movie I really love. And when I saw my scene, I discovered that it was also referential of that movie. Then I thought that was not what I wanted. [Roma’s production designer] Eugenio Caballero told me it was a beautiful scene. “Yes, it’s beautiful because it’s someone else’s, not this movie’s,” I told him. The other one is more beautiful, but this is the right one. It doesn’t mean there are no references at all, because, just as in our lives, you are what you’ve been. In filming, you are what you’ve watched and read and listened to — and not just from movies.

You’ve said before that “Roma” is also loosely based on your childhood. Were you able to exorcize any inner demons while making the film?

Every human experience related to a long-lasting project always is going to have a transformative part. When you start a job that takes longer than the average task, you go into a parallel reality. An abstraction begins, and everything outside your project seems to flow at a different pace. It flows differently. And when you reconnect with that reality, you feel the difference. Sometimes that difference creates transformations. Sometimes it’s kind of a shock, but that’s it. In “Roma,” specifically, any human experience focused on its own memory will inevitably have emotional consequences.

But you’re the one who is changing, right?

No, the universe is the one changing! [Laughs.] That’s not true — of course we’re changing. What changes in the universe is your perception about it. The universe doesn’t give a damn about you. In “Roma,” every person willing to focus on their memories is going to discover something. Those might be joyful or unpleasant discoveries. To face your memory is to face what you were back then that still lives inside your subconscious. “Roma” was a three-year process of living in memories, and not only living, but opening doors from the memory labyrinth. And as soon as you open a door, you find new corridors with new doors, and then every time you open a new door you find new corridors. The more you focus on this labyrinth, the more you get lost in it.

“Roma” is in theaters and on Netflix in December. Instagram: @alfonsocuaron.