A new book looks at Southern generals, governors and others who preferred exile over life under Union rule

by Rich Tenorio

As the United States’ Civil War ended in 1865 and many defeated Southern cities lay in ruins, a handful of ex-Confederates who ended up leaving their ill-fated secessionist nation opted for a perhaps unlikely destination: Mexico.

The narrative of what happened to members of the Confederate army after the war’s end is addressed in a new book about this period of history: Ends of War: The Unfinished Fight of Lee’s Army after Appomattox by University of Virginia professor Caroline Janney.

“It quickly became clear there were so many unanswered questions and so many unanticipated consequences, questions that other people had not asked,” said Janney of what inspired her book, which took six years to research and write.

In 2022, it won the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

Janney said her interest began with one question – “what do you do with the Confederate army, a rebel army, after a civil war?” She reflected, “It started as a simple question and blossomed into a whole host of questions.”

“I was most surprised,” she said, “to find out the number of men who didn’t surrender themselves at Appomattox, those who pursued the slim opportunity to continue waging the war.”

Confederate General Jubal Early is perhaps one of the more prominent of these ex-Confederates who ended up in Mexico for a while after the war; he led troops in some of the Civil War’s bloodiest and most famous battles, including Antietam, Fredericksburg and Gettysburg.

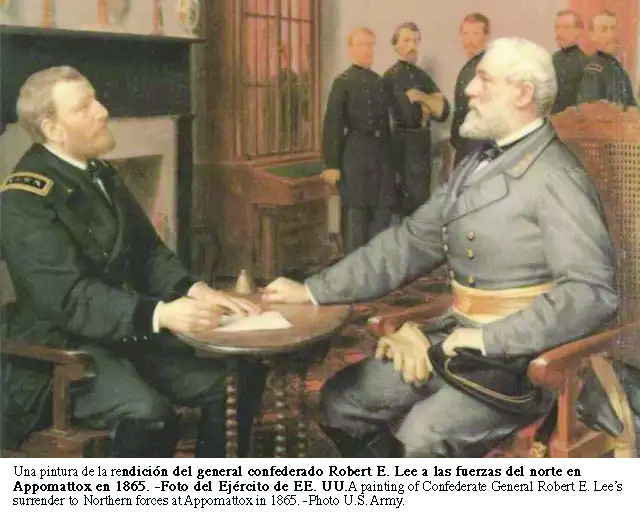

Defeated in battle, Early was relieved of his command by General Robert E. Lee in March 1865, just a month before Lee himself surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, widely seen as ending the Civil War.

Early and other defeated Confederates, including oceanographer-turned-rebel navy secretary Matthew Fontaine Maury, fled to Mexico in the war’s aftermath. Early decided he would not live under the United States government and fled to Texas on horseback, then on to Mexico.

Maury, who would develop a doomed plan for resettlement of ex-Confederates via land grants from the Mexican government, followed a more circuitous path that included a stop in England.

Most of those who journeyed to Mexico did so via steamship, although others traveled overland to New Orleans, and then to Texas.

Some who reached Mexico included generals and governors invited by Mexico’s Emperor Maximilian, who was a longtime friend of Maury’s. Confederate generals who came to Mexico at Maximilian’s behest included John B. Magruder, Sterling Price, Joseph Shelby and Edmund Kirby Smith.

“They no longer considered themselves U.S. citizens,” Janney explained of ex-Confederates heading across the Rio Grande. “They see [Mexico] as a better alternative to being subjugated by the enemy.”

Another motivation of these men was the possibility of fighting against the U.S. again if war broke out over Mexico between the United States and France. With the Civil War over, the U.S. had sent soldiers to the Mexican border, including members of the U.S. Colored Troops, with the intention of enforcing the Monroe Doctrine against foreign involvement in the Americas.

A war between the two countries didn’t seem out of the realm of possibility.

Even before the war had ended, as things were looking their worst for the South, apparently some were already considering picking up the fight against the Union from elsewhere: Janney’s book quotes a 23-year-old Confederate officer in Robert E. Lee’s army named William Gordon McCabe. He considered fighting against the U.S. under a different flag.

On April 7, 1865, two days before Lee’s surrender, he wrote, “I am willing and ready, if God spares my life, to follow the old battle flag to the Gulf of Mexico. If our men desert it, and I am not killed, I shall be forever an exile.”

On April 25, McCabe had journeyed from Virginia to North Carolina and was considering the possibility of a war between France and the U.S., “when we may probably get something to do in the service of H. S. H. [His Serene Highness] Napoleon III.”

By that point, U.S. president Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated on April 15 by Southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth, inflaming Northern hostility toward the South. This gave those who fled to Mexico yet another reason to consider leaving.

“Why were they willing to go to a country where the unknowns were so great?” she asked. “They feared retribution, they feared punishment within the U.S.”

Some former Confederates fled even further abroad than Mexico, refusing to live in a country with emancipated slaves; Mexico had ended slavery before the U.S. did. These men headed to two other Latin American countries where slavery still existed: Cuba and Brazil.

There were some ironies in Confederates fleeing the U.S. for Mexico: some had been there almost two decades earlier, fighting for the U.S. in the Mexican-American War.

“A lot of the [Confederate] officer corps was familiar with Buena Vista,” Janney said, referring to the 1847 battle between the Mexican army of Antonio López de Santa Anna and the U.S. force of Zachary Taylor. “It was not completely foreign to them in that regard.”

Some Confederates fled to Mexico to save their lives: two months after General Lee surrendered, he was indicted for treason on June 7, 1865, a fate shared by 36 fellow Confederates, including Jubal Early.

A treason conviction meant death, which pushed Early to become an expatriate in Mexico.

Some who came to Mexico committed fully to a new life here and planned to live in Maury’s and other settlements for ex-Confederates in a number of states, among them ones in modern-day Coahuila, Tamaulipas, Nuevo León and Morelos.

Others realized that they had clearly made a spontaneous, angry decision to leave the U.S. and didn’t make it past Texas.

“Some of this clearly is a reaction that’s not especially well-thought-out in terms of long-term circumstances,” she said. “Going to Texas, many changed their mind within one month or two. Their immediate response, full of emotion and rage, tempered itself.”

anney said she was struck by those who did make it to Mexico.

“It speaks not just to their devotion to the Confederate cause, but their rejection of the U.S.,” she said.

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.