by the El Reportero’s staff

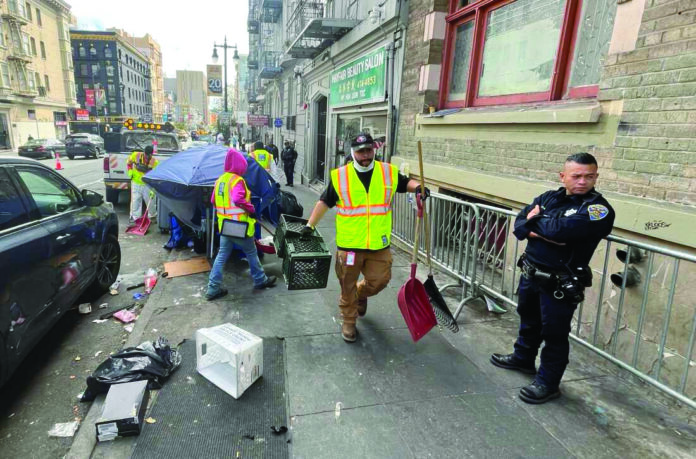

Despite billions spent over the last decade, the San Francisco Bay Area’s homelessness crisis continues to grow — driven by soaring rents, mental health and addiction challenges, and most critically, a lack of coordination between cities and counties.

The structural divide in California’s system exacerbates the issue: cities are tasked with building shelters and housing, while counties handle behavioral health and addiction services. Without close collaboration, critical gaps emerge, and many fall through the cracks. From San Francisco to San Jose, political leaders push bold strategies — often in conflict with each other and lacking cohesive support.

San Francisco: Service cuts vs. prevention initiatives

In San Francisco, Mayor Daniel Lurie’s $15.9 billion budget for 2025-26 includes deep cuts to homelessness programs, slashing funding for nonprofits that provide food, shelter, and other support. Advocates warn this will destabilize already vulnerable populations and undermine past progress.

Simultaneously, Lurie launched the Family Homelessness Prevention Pilot, partnering with Tipping Point Community. The 18-month initiative aims to keep families housed by offering cash aid, employment support, and legal assistance. While the concept has been praised, many question its viability amid broader budget reductions.

“There’s a contradiction in cutting services while launching new ones,” a Coalition on Homelessness representative said. “You can’t prevent homelessness if you’re also defunding the safety net.”

San Jose’s “responsibility to shelter” sparks debate

In San Jose, Mayor Matt Mahan introduced a “Responsibility to Shelter” policy that would penalize individuals who refuse shelter more than three times in 18 months, potentially leading to misdemeanor charges if they remain in encampments.

Mahan argues the city has invested significantly in interim housing — from tiny home villages to motel conversions — and believes residents should be required to accept shelter when it’s available.

“We’ve built the shelter. We’ve built the housing. Now we need a framework to require people to use it,” Mahan said.

Critics, including civil rights advocates and Santa Clara County officials, argue the policy is punitive and may criminalize people who avoid shelter for valid reasons, such as past trauma or restrictive facility rules. Santa Clara County, responsible for healthcare and case management services, has not endorsed the policy. Supervisor Susan Ellenberg stressed that counties cannot be expected to support growing city programs without a say in their design or funding.

“Cities can’t keep building and expect counties to endlessly fund support services,” Ellenberg said. “We need planning — not mandates.”

Oakland and Alameda County: A disjointed partnership

In Oakland, the divide between city and county is especially stark. The city handles shelters and outreach, while Alameda County manages behavioral health and supportive housing. But collaboration has been lacking.

When Oakland dismantled the large Union Point Park encampment in 2023, some residents were offered shelter — others were simply displaced. Advocates say the county failed to deploy needed mental health teams, leaving vulnerable individuals without help.

A 2022 Alameda County Grand Jury report highlighted the dysfunction, citing confusion, redundancy, and poor outcomes due to the absence of unified governance. Though some leaders have floated the idea of a regional homelessness authority, no substantial action has followed.

Fremont: Enforcement without infrastructure

In Fremont, officials have taken a harder stance, passing a controversial ordinance that bans camping in specific areas and punishes those who “aid and abet” the unhoused. Critics say the law is overly punitive, especially since Fremont lacks permanent shelter beds and relies on county-run facilities, which are often full.

“Fremont criminalized homelessness without offering a realistic alternative,” said a legal advocate with the ACLU of Northern California. “That’s not governance — that’s abdication.”

The city says the ordinance is intended to protect public spaces and encourage shelter use, but without adequate housing options, advocates view the policy as symbolic enforcement over real solutions.

Cities vs. counties: An undefined relationship

Throughout the Bay Area, the homelessness response is hampered by the lack of a formal structure outlining shared responsibilities between cities and counties. With budget pressures mounting, each side blames the other. Cities hesitate to fund services viewed as county obligations, while counties resist city-driven expansions that require ongoing support.

Senate Bill 16, a recent legislative effort, proposed requiring counties to cover 50% of city shelter costs to qualify for state homelessness funds. However, county opposition led to the bill being gutted. San Jose’s Mahan backed the bill, warning that cities are “at capacity” and cannot expand services without shared accountability.

“We’re leaving people outside because the system isn’t scaling,” Mahan said.

Conclusion: A call for unified action

The Bay Area’s homelessness crisis is not just a funding issue — it’s a governance failure. While cities move at varying speeds, counties face limits without influence over policy direction or budget control. Without a statewide mandate or regional coordination framework, efforts remain fragmented and often counterproductive.

As cities like San Francisco launch new programs while cutting existing ones, San Jose pursues enforcement-based strategies, and Oakland and Fremont struggle with disconnected policies, the overarching issue remains clear: disjointed leadership is blocking meaningful progress.

Until cities and counties align on responsibilities, funding, and goals, the region’s unhoused population will continue to suffer from the consequences of bureaucratic dysfunction.

– With reports from CalMatters and wire services.