Legal challenges to an extremely narrow vote are a fundamental part of democracy

por Mary Anastasia O’Grady

Shared from the Wall Street Journal

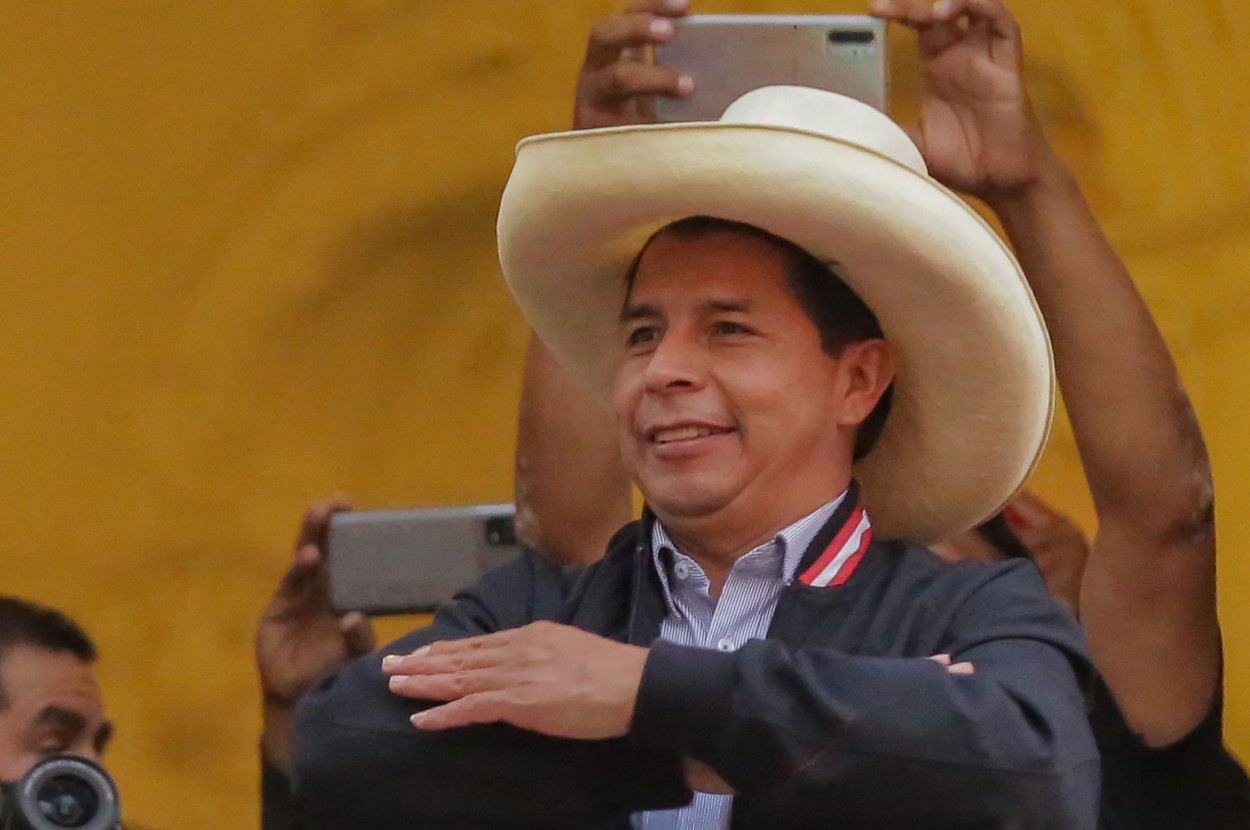

June 20, 2021 – During the Peruvian presidential campaign earlier this year, socialist candidate Pedro Castillo told voters that he would nationalize the assets of foreign investors. He did not say whether this would apply to Chinese corporations that own billions of dollars of Peruvian mining interests. But predicting that it won’t isn’t exactly going out on a limb.

Mr. Castillo is a rabid anticapitalist backed by Peru’s extreme left. He’s a perfect partner for Beijing, which doesn’t even pretend to care about corruption or human rights. China is eager to increase its political and economic influence in South America, and it made inroads into Peru when, in May 2019, then-President Martin Vizcarra —who was later impeached on corruption charges and removed from office—signed on to its Belt and Road Initiative.

The China card that Mr. Castillo is expected to play is one reason Peruvians, along with the U.S. and other democracies, have an interest in a transparent review of contested votes from the June 6 runoff presidential election. But it isn’t the only one.

The difference between vote totals for Mr. Castillo and his center-right rival, Keiko Fujimori, is extremely narrow. If Mr. Castillo is declared the winner he has threatened to use his slim majority as justification to tear up the country’s economically liberal constitution and replace it with something closer to Venezuela’s. It isn’t hyperbole to say that he believes that 50.1% of the vote entitles the winner to steamroll the rights of the other 49.9%.

This is no reason to deny Mr. Castillo a victory if he won fair and square. But it strengthens the case for maximum transparency, which can only be guaranteed by an impartial hearing for both sides. If Mr. Castillo can be taken at his word, Peruvian freedom is at stake.

On June 10, 17 former presidents from Latin America and Spain issued a declaration calling on both parties to exercise leadership by waiting for Peru’s electoral authorities to complete their oversight responsibilities.

Mr. Castillo’s camp says the outcome is already decided because he’s ahead by around 44,000 votes after some challenges have been resolved by electoral authorities. Ms. Fujimori says that some 200,000 more votes—the majority in favor of Mr. Castillo—ought to be nullified because of fraud. She says she can prove it if the electoral council releases the data and the tribunal agrees to hear the evidence.

Mr. Castillo’s supporters, claiming to love democracy, want to deny that possibility. Alberto Fernández, Argentina’s leftist president, tweeted congratulations to Mr. Castillo days after the election, adding some mumbo-jumbo about the country’s “institutional strength.”

But it’s too early to draw the conclusion that institutions have worked. First Peruvians must be permitted to challenge the election results, as is their right under Peruvian law.

Some not-very-bright opponents of Donald Trump had meltdowns last fall when I suggested that Trump challenges should be allowed to play out in court. They were wrong. By allowing judges—many of whom were named by Republicans—to review claims of massive fraud, the process played out legally.

Peruvians deserve equal treatment and transparency, and public trust in institutions requires as much. Petitions for access to the legal system not only are legitimate but would clarify the results.

It is likely that Mr. Castillo understands this better than most. In what appears to be an effort to close the matter quickly, he has withdrawn his appeals not yet heard by the national electoral tribunal.

That tribunal, which decides what appeals will be heard, is off to a rocky start. It has five seats but only four are filled. The president of the tribunal, whose sympathies with the left are well established, is by law the tie breaker.

The tribunal asks for challenges to be filed within three days of the election, with proof that lawyers have paid the required fee. Hundreds of challenges are hanging in limbo because the tribunal has not yet decided if failure to comply with such technicalities ought to render them invalid.

Lawyers for Ms. Fujimori argue that the court needs to consider her challenges on the merits rather than arbitrary deadlines. The tribunal seemed to have some empathy for that argument on Friday, June 11, when it ruled that it would accept late challenges. Later that same day it reversed its own decision, sparking speculation that it is under enormous pressure from the left to rush through a Castillo victory.

If Mr. Castillo cheated, with the help of political allies like Cuban-trained Vladimir Cerrón —who heads Mr. Castillo’s Peru Libre Party—then Peruvians deserve to know. If he didn’t cheat and the nation voted, however narrowly, for a candidate who has repeatedly promised to blow up the market economy, they deserve to know that too.