by Ryan Devereaux

The Intercept

First of two parts

THE FOOTAGE IS unquestionably dramatic: Members of Mexico’s most elite security forces clear a four-bedroom house in a predawn raid. Over the course of 15 chaotic minutes, the Mexican marines can be seen moving room to room through the smoky building. Gunfire thunders. The walls are pocked with bullet holes. The commandos toss grenades. A marine goes down. “They got me,” he screams. The marines detain an unidentified individual with flex cuffs and find two women hiding in a bathroom. Garbage and high-powered rifles litter the floor.

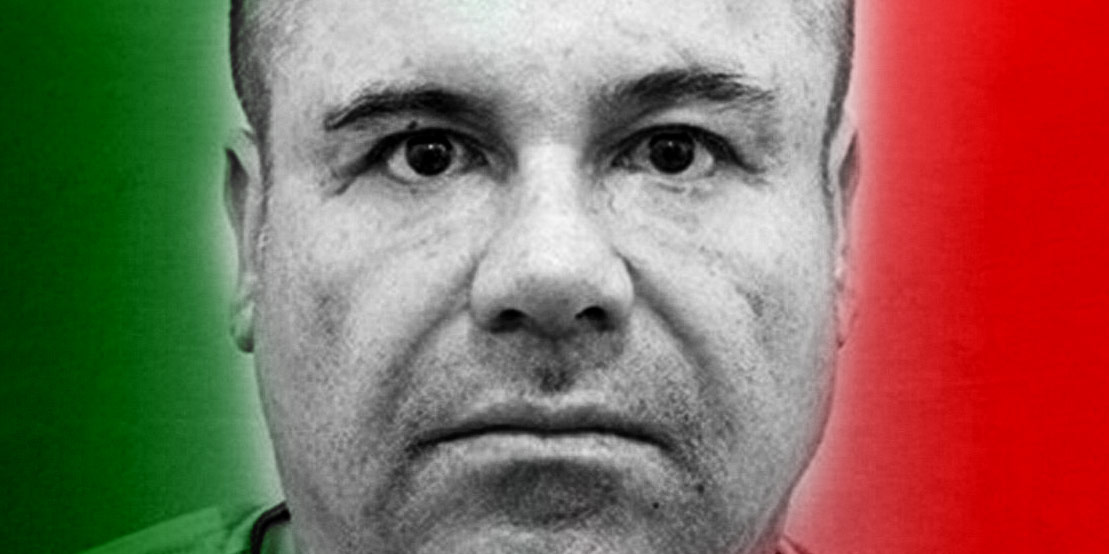

The narrative that follows the gunfight is every bit as fast-paced. When the smoke cleared, four people were under arrest, with five more reported dead. Photos of their bloody bodies appeared online the next day. Two others escaped, however — one of them a stocky, bearded man named Ivan Gastelum, the alleged assassin-in-chief for the Sinaloa cartel, Mexico’s most powerful and sophisticated drug-trafficking organization. Gastelum, who goes by the nickname “El Cholo Ivan,” was accompanied in flight by his boss, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera, the world’s most infamous drug trafficker and Mexico’s most wanted man.

According to a video of the raid obtained by Mexico’s Televisa network, which published the footage Monday accompanied by interviews with marines who took part in the operation, Gastelum and Guzmán relied on a familiar trick to elude the well-armed men bearing down on them: They dropped into a tunnel, the same tactic Guzmán had famously used six months earlier when he escaped from Mexico’s top maximum security prison, the second early exit from incarceration of his storied criminal career. This time around, Guzmán’s route to freedom was apparently hidden behind a closet mirror. It reportedly took an hour and a half for the marines to locate the lever, hidden in a ceiling fan, which allowed them to access the tunnel.

According to some media accounts, the marines entered the passage carrying torches.

Gastelum and Guzmán used their head start to escape through the sewer system of Los Mochis, a coastal city in Guzmán’s home state of Sinaloa. Upon emerging, the men stole a vehicle, which ran out of gas. So they stole another. The driver of the second vehicle called in the theft, authorities said, permitting security forces to capture the pair alive. They were taken to what The Guardian described as “a sex motel,” complete with a “laminated menu of sex toys, condoms and lubricants,” before being handed over to the military. Speaking to Televisa, the head of the Mexican special operations unit, the same man said to have captured El Chapo in 2014, said he told the drug boss, “Your six-month vacation is over,” to which Guzmán replied, “Yes, my holiday is over.”

And so ended Operation Black Swan. Of course, how much of that story is true remains to be seen. Initial accounts of high-stakes military raids, particularly those with profound political implications, are notoriously prone to inaccuracies and often take years to sort out, regardless of the country in question. The raid that killed Osama bin Laden is but one prominent example. In Mexico, where it is not uncommon for journalists covering drug-related violence to be killed on the job, or for the government to obfuscate facts, the truth can be especially difficult to pin down.

Arturo Fontes, a former FBI investigator who spent nearly 30 years working drug cases in Mexico, much of that time focused on the hunt for Guzmán, applauded the drug lord’s arrest. At the same time, however, he suggested that broader political motivations, particularly the current record low value of the Mexican peso, might have played a role in triggering the raid. “I believe that Chapo could have been arrested about two months, or six months ago,” Fontes told The Intercept.

When Mexican authorities commit themselves to making arrests, Fontes argued, they often succeed. The problem, he said, is one of will and corruption. “They have the people, they have good police officers, a good military,” he said. “It’s corruption [that] gets the best of it.” That corruption, which Guzmán no doubt has intimate knowledge of, is likely making a number of Mexican politicians, business people, and law enforcement and military officials uneasy now that he is in custody, Fontes added.

Some have already begun calling the official account of Guzmán’s arrest last weekend into question. The novelist Don Winslow, who has written two heavily researched, fictionalized accounts of the drug war in Mexico based largely on Guzmán’s real-life rise to power, has repeatedly slammed the official narrative on Twitter, pointing to a Reuters report that found “no signs of bullet holes” on the exterior of the building where Guzmán’s men died. Noting edits in the raid footage and the fact that none of Guzmán’s men were shot on camera, Winslow also tweeted, “Dear President Nieto … Please release the UNEDITED video of the El Chapo ‘raid’ to the American media.”

The extent to which Mexican security forces received help on the ground during last week’s events remains unclear. While there is little question that U.S. intelligence aided in the run-up to the operation, the official line out of Mexico City has credited Mexican security forces with the capture. Yet Reuters, citing a senior Mexican police source and a U.S. source, reported that U.S. marshals and DEA agents were “involved” in Guzmán’s capture.

Such cooperation is commonplace. The Wall Street Journal has reported that U.S. marshals have made a practice of dressing as Mexican marines and joining in armed drug raids in recent years. The Mexican investigative newsmagazine Proceso, in a story sourced to two American officials in Washington, D.C., reported that El Chapo was last apprehended by American members of the Marshals Service, the DEA, and an unnamed U.S. intelligence agency wearing the uniforms of Mexican marines.

On Monday, SOFREP, a news website run by U.S. special operations veterans that covers secretive missions around the world, added a new wrinkle to the evolving account of Guzmán’s capture, reporting that members of the U.S. Army’s Delta Force were also on the scene during the mission. Attributed to multiple anonymous sources, the article reported that the U.S. marshals played an “important role in tracking down the drug lord” and that Delta commandos, part of the U.S. military’s super-secretive Joint Special Operations Command, “served as tactical advisors but did not directly participate in the operation,” adding that “law enforcement agencies are said to regard the presence of a JSOC operator as a sort of lucky talisman.”

An assist from the U.S. military’s most elite fighters in taking down a major Latin American drug trafficker would not be unprecedented. In his book Relentless Strike: The Secret History of Joint Special Operations Command, journalist Sean Naylor delves into the role U.S. special operations forces, including members of Delta Force and SEAL Team 6, played in tracking down Colombian kingpin Pablo Escobar nearly two-and-a-half decades ago. Naylor explains how the mission, which was technically supposed to be limited to training elite Colombian security forces but led to Escobar’s death on Dec. 2, 1993, capitalized on communications surveillance and laid the groundwork for the so-called high-value targeting missions that would come to define JSOC’s role in a post-9/11 world.

Fontes said he did not believe U.S. elements were directly involved in Guzmán’s most recent capture. “Not on this one,” he said. “There’s been a lot of information sharing on telephone numbers, on key people,” Fontes said. “Whether the information was not shared this time, it’s been shared in the past.”

Carl Pike, a former assistant special agent in charge of the DEA’s special operations division, who retired in Dec. 2014 after Guzmán’s second arrest, said he had no information on U.S. personnel actively participating in Guzmán’s most recent apprehension. Typically, he explained, “When it gets down to the nut-cutting itself, the actual act, it’s all GOM [government of Mexico].” READ SECOND PART OF THIS STORY NEXT WEEK.