Shared from AP’s Amy Taxin

LOS ANGELES (AP) – It took nearly a decade and a federal lawsuit for U.S. Marine Corps veteran Hector Ocegueda to finally come home.

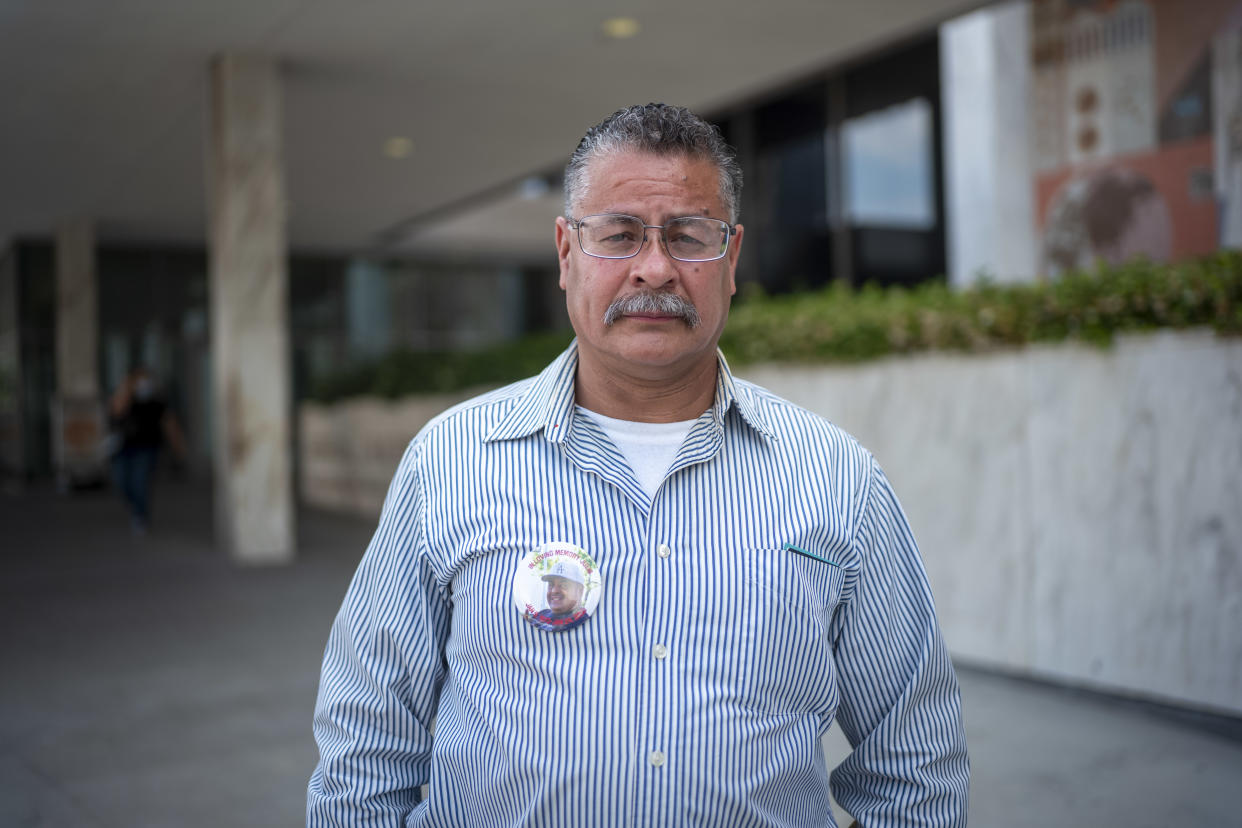

Following a conviction for intoxicated driving, he had been deported to Mexico, a country he left with his parents from him when he was a child. The 53-year-old has spent the past nine years living in Mexico but on Friday, he will take the oath to become an American citizen – a step that allows him to return to his family in Southern California.

While in Mexico, Ocegueda applied to become an American citizen after connecting with a group for deported veterans. Under U.S. law, veterans who serve honorably during a conflict are eligible to become citizens if they meet a series of requirements, including undergoing an interview with a citizenship officer.

He had been scheduled for the interview in Los Angeles last year but couldn’t attend because border authorities wouldn’t allow him back into the country following his deportation order.

Ocegueda sued last month, asking U.S. officials to give the citizenship interview on the border, where he could attend, or allow him to cross so he could make an appointment in Los Angeles, which is what happened this week.

“It felt that I was coming back home when I crossed that border. I was so happy, ”he said.

To U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services officer interviewed Ocegueda on Thursday. A day later, he is scheduled to take his citizenship oath before a judge in Los Angeles.

“I know the system is not perfect. I am mad at the system – but not at this country, “Ocegueda said before attending the ceremony with his sister and other relatives.” I love this country. ”

The case comes as the Biden administration has stepped up efforts to reach out to noncitizen military members and veterans. Last week, the Departments of Homeland Security and Veterans Affairs announced plans to identify deported veterans, ensure they can access benefits they are entitled to and remove barriers to naturalization for current and former service members who are eligible to become American citizens.

The American Civil Liberties Union issued a report in 2016 detailing the cases of dozens of veterans who were deported or facing deportation, many over convictions for minor crimes. Had these veterans become citizens on account of their military service, they wouldn’t have been deported.

Ocegueda was brought to the United States from Mexico by his parents and grew up in the Southern California city of Artesia. He served in the Marine Corps from 1987 to 1991 and spent four more years in the reserves before he was honorably discharged. He got married, had two daughters and obtained a green card through his wife from him.

But Ocegueda also had a drug problem. He was convicted of driving under the influence, prompting U.S. immigration officials to deport him in 2000, his lawyers said.

Despite that order, Ocegueda returned to California to be with his family from him and participated in a drug treatment program through a local veterans hospital. But he was deported two more times. Since 2012, Ocegueda says he has remained in Mexico, where he worked as a driver and a security guard and connected with the leader of a group for deported veterans who encouraged him to stay put so he could pursue citizenship.

It came at a cost. It was difficult to adjust to life in a country he had left when he was a boy. But nothing compared to the hurt of being away from his family of him. His marriage of him was suffering, and he wound up divorced. I have missed out on time with his daughters. And he was lonely; he said his relatives of him often had to work and could not make the trip down to see him as often as he would have liked.

Now, Ocegueda said he hopes to go back to school so he can work as a nurse assistant, find a job and spend time with the people he loves.

“I am going to take it day by day,” he said. “It’s great to be here with them.”