by David Bacon

NAFTA had been in effect for just a few months when Ruben Ruíz got a job at the Itapsa factory in Mexico City in the summer of 1994. Itapsa made auto brakes for Echlin, a U.S. manufacturer later bought out by the huge Dana Aftermarket Group. In the factory, asbestos dust from brake parts coated machines and people alike. Ruiz had hardly begun his first shift when a machine malfunctioned, cutting four fingers from the hand of the man operating it.

It seemed clear to Ruiz that things were very wrong, so he went to a meeting to talk about organizing a union. When Itapsa managers got wind of the effort, they began firing the organizers. Nevertheless, many of the workers joined STIMAHCS, an independent democratic union of metalworkers.

Itapsa workers filed a petition for an election, but then discovered that they already a “union” – a unit of the Confederation of Mexican Workers (CTM). They’d never seen the union contract – in essence, a “protection contract,” which insulates the company from labor unrest.

The plant’s HR manager told Ruiz that Echlin management in the U.S. said any worker organizing an independent union should be immediately fired. “He told me my name was on a list of those people,” Ruiz recounted, “and I was discharged right there.”

Nevertheless, there was a vote, in September 1997, to decide which union workers wanted. But before the election, a state police agent drove a car filled with rifles into the plant. Two busloads of strangers arrived, armed with clubs and copper rods. During the voting, workers were escorted by CTM functionaries past the club and rifle-wielding strangers. Some workers were forcibly kept in a part of the factory to keep them from voting. At the polling station, employees were asked aloud which union they favored, in front of management and CTM representatives.

STIMAHCS tried to get the election canceled. But the government body administering it, the Conciliation and Arbitration Board (JCA), went ahead, even after thugs roughed up one of the independent union’s organizers. Predictably, STIMAHCS lost.

For 20 years the Itapsa election has been a symbol of all that’s gone wrong with Mexico’s labor law, which provides protection on paper for workers seeking to organize but which has been routinely undermined by a succession of governments bent on using a low-wage workforce to attract foreign investment. Dana Corporation was just one beneficiary – Itapsa has been the norm, not the exception.

In 2015 thousands of farm workers struck U.S. growers in Baja California. Instead of recognizing their new independent union, however, growers signed protection contracts with the CTM, which were certified by the local JCA. Strikers were blacklisted. Later that year workers tried to register an independent union in four Juarez factories. Some 120 workers making ink cartridges for Lexmark were fired, as were another 170 at ADC Commscope, and many more at Foxconn and Eaton.

The labor board declined to reinstate the fired workers in Juarez and Baja – following the pattern it had set at Itapsa two decades earlier. Indeed, the JNCs have been key to the defeat of workers’ attempts to form democratic unions, invariably protecting employers and corporate-friendly unions.

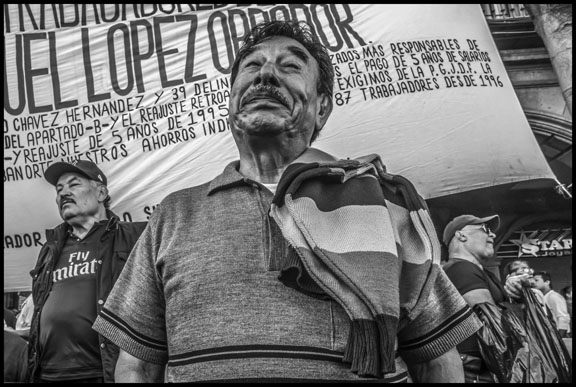

The new Mexican government, headed by President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO), says that’s all over. Deputy Secretary of Labor in the new administration, Alfredo Dominguez Marrufo, promises that, “after all these struggles, we can finally get rid of the protection contract system. We can make our unions democratic, choose our own leaders and negotiate our own contracts. This government will defend the freedom of workers to organize.

That right has existed in theory, but we’ve had a structure making it impossible. This will change.”

That could have a big impact on political life in Mexico, where corporate union leaders have had an inside track to political power and corruption. It could change the dominating role U.S. corporations have played in the Mexican economy, and affect relations between workers in both countries. Most of all, it would raise a standard of living for workers that Lopez Obrador has called “among the lowest on the planet.” In his speech to the Mexican Congress during his December 1 inauguration, the new president charged that 36 years of neoliberal economic reforms had lowered the purchasing power of Mexico’s minimum wage by 60 percent. Today, on the border, that wage comes to a little above $4 per day. (President López Obrador announced that salaries in border states with the US would increase the minimum wage twice as much).

According to University of California Professor Harley Shaiken, “The Mexican government created an investment climate that depends on a vast number of low wage-earners. This climate gets all the government’s attention, while the consumer climate – the ability of people to buy what they produce – is sacrificed.”

Protecting corporations from demands for higher wages has made Mexico a profitable place to do business. Big auto companies, the world’s major garment manufacturers, the global high tech electronic assemblers – all built huge plants to take advantage of Mexico’s neoliberal economic policies, starting more than two decades before the negotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

That wild-west climate for investors produced more than low wages, however. Between 1988 and 1992, 163 Juarez children were born with anencephaly – without brains – an extremely rare disorder. Health critics charged that the defects were due to exposure to toxic chemicals in the factories or their toxic discharges. The Chilpancingo colonia below the mesa in Tijuana where the battery plant of Metales y Derivados was located experienced the same plague.

(Due to the length of this article, it has been cut to fit space. You can read the full piece at: https://prospect.org/article/new-day-mexican-workers).