They need protection from covid-19, too

by Katie Peeler

– As a pediatric intensive care physician, I like to think I have an unusually strong stomach for heart-wrenching scenarios. While they impact me deeply, I am not easily rattled.

But COVID-19 has rattled me. Everyone I run into is experiencing extreme anxiety over the uncertainty of what lies ahead. How many people will get sick? Will our local hospital run out of ventilators? Will my parents die? Will I die?

Imagine these questions not between adults, but between two school-aged siblings. Perhaps their parents overhear them and can quell some of their anxieties. My own son, only 5-years-old, could not fall asleep last night because at school last week he heard that “billions of people were going to die.”

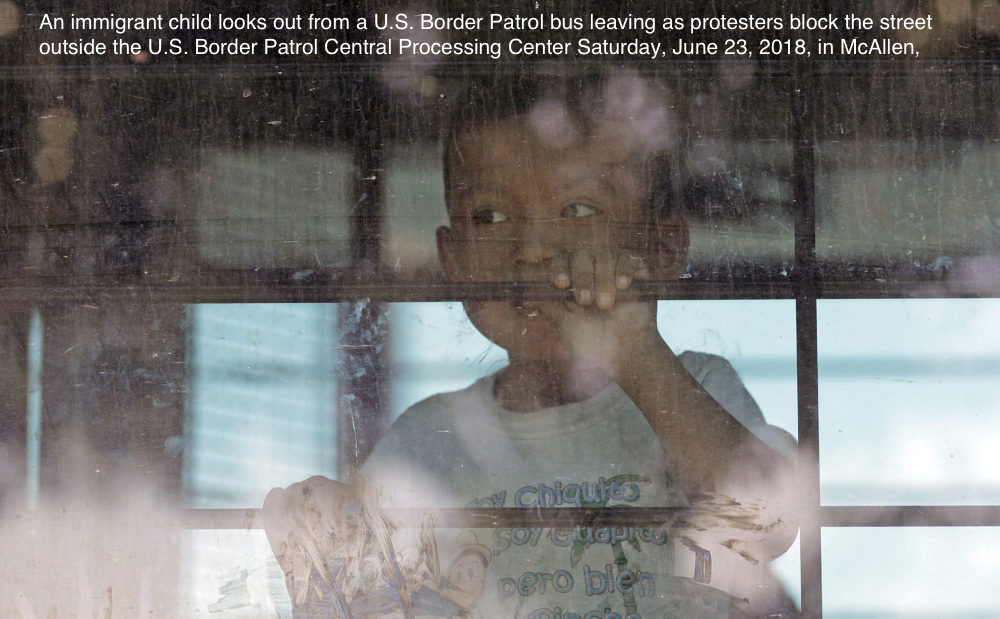

Now imagine these questions, as asked by immigrant children detained in crowded shelters thousands of miles away from their parents. They are terrified, and the people they worry about most — and who they most need to love and comfort them — aren’t there.

While we are all justifiably concerned for our own children in these fraught times, we must not forget this particularly vulnerable group of children in the United States. They are just as deserving of protection during this pandemic.

Children younger than 18, who arrive at the U.S. border without a parent or guardian, are first held in border cells run by the Department of Homeland Security. Federal law requires that they be transferred within 72 hours to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), which is under the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). The number of such children arriving annually is growing — almost 70,000 in 2019. Some ORR facilities are foster homes, which may offer better care, but others are group homes or large shelters that may house more than 1,000 children at a time.

The vast majority of these children come from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador — countries notorious for rampant gang violence and governments unable or unwilling to intervene. After often long and extremely dangerous journeys, they arrive at the Mexico-U.S. border already severely mentally and physically traumatized — a fact I can testify to as a medical expert with Physicians for Human Rights.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 globally has made starkly clear how critical it is to take preventative action. The current system of detaining children in ever larger groups, and for longer periods of time, increases their severe health risks and the likelihood of human rights violations.

In crowded settings, how is ORR able to follow the CDC’s guidance about social distancing and appropriate personal hygiene? Have they reviewed these guidelines with their staff or with the children? Attorneys with Kids in Need of Defense (KIND), a nonprofit organization that provides legal services to children in ORR custody, visited a shelter within the last week. There, they found diluted soap in the bathrooms, large groups of children crowded in a room for their legal screenings and no evidence of sanitizing the room before or after.

We’re in the middle of a global pandemic — none of this is acceptable.

We all want to protect our children and those we love. We cannot forget about the ones we cannot see.

New data from more than 2,000 pediatric cases in China indicates that young children are vulnerable to COVID-19, with severe and critical cases of children particularly noted in infants. While this is lower than adult rates, it still may represent a significant number of vulnerable and sick children. Unfortunately, there has been a history of delayed recognition of both underlying medical disorders and acute illness in detained children. ORR must take every precaution and implement creative solutions to shield children and staff from unnecessary harm.

Also of paramount importance to these children’s well-being is protecting their caregivers.

Reports from China and Italy indicate that many otherwise well children who contract this new virus are frequently asymptomatic or present with symptoms of the common cold. In the context of a crowded shelter or detention center, it is not uncommon for children to have minor colds. Without ready access to testing, it is impossible to know which virus a child has. Spread of COVID-19 will be quick. Caregivers in the shelters could also fall ill. What is the back-up plan for caring for these children if the shelter workforce is quickly depleted?

Policy change is slow, but pandemics wait for no one.

Migrant children also have significant mental health needs, given the trauma they endured at home, during their journeys, and in becoming a ward of our government. Their lives are already filled with anxiety and uncertainty.

A recent report from the Office of the Inspector General showed that despite specific guidelines that dictate the type and frequency of mental health services required for each child to receive, the actual mental health resources available in ORR shelters is far below the requirement. This need will increase exponentially in these children as their anxiety heightens with the pandemic.

Policy change is slow, but pandemics wait for no one.

DHHS must step-up high-level screening for safe sponsors of children immediately upon arrival to the border. They must expeditiously place children with such sponsors, thereby avoiding feeding into an already overcrowded shelter system.

Further, ORR must ensure all staff and children understand the CDC guidance surrounding social distancing and personal hygiene and robustly stock their shelters with soap, hand sanitizer, cleaning supplies and food. Medical triage guidelines must be clear and practiced, and mental health support should be provided for all.

Immigration court proceedings for detained children should be halted for now, and flexibility should be given to legal services organizations so they can utilize videoconferencing or individual meetings when possible.

The ORR facilities are spread out across the U.S., and there may be one or more in your state. You can encourage your local, state or national representatives to exercise oversight of ORR to ensure they are acting in the best interest of children, as well as their families and caregivers.

We all want to protect our children and those we love. We cannot forget about the ones we cannot see.