A French artist’s colossal installation on Mexico’s side of the border may make the invisible visible, but other subjects carry a sharper critical edge and pose deeper questions

by David Bacon

First person

(This article originally ran at Capital & Main, an award-winning publication that reports from California on economic, political, and social issues.)

For almost an hour, Laura, Moises, and I drove through the dusty neighborhoods of Tecate, looking for Kikito. Tecate is a small border city in the dry hills of Baja California. It’s famous for a huge brewery, although today most workers find jobs in local maquiladoras.

When we asked for directions, a couple of people had heard of Kikito, but couldn’t tell us where he was. Most didn’t know who we were talking about.

We figured that if we kept driving along the border fence, we’d find him. In these neighborhoods, the second stories of large comfortable homes, mostly built in the 1940s and 1950s, rise above adobe walls enclosing their courtyards. But unlike downtown, with its colorful bustle, there was no street life on the hot streets here, hardly anyone on the sidewalk.

Finally, we passed the one man who could surely tell us how to find Kikito—the cable guy. He even volunteered to lead us in his van part of the way. Using his directions, we bumped along a dirt road next to the border fence, up and down a couple of hills where the city fades into scrubland. Then we found Kikito.

He was much larger than I’d imagined.

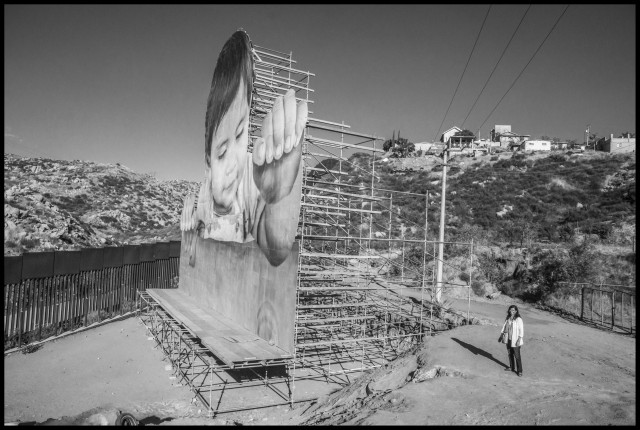

Kikito is an enormous photograph of a 1-year-old child, pasted onto plywood sheets. The assemblage is mounted on a huge, complex metal scaffold, 65 feet high, much like what painters erect to embrace the buildings they work on. Kikito’s scaffolding, however, doesn’t embrace anything. Instead, it pushes the enormous photograph toward, and above, the border wall’s severe vertical iron bars.

The structure is so big that to bring the photo into position, part of the hillside had to be excavated, and a hole dug deep into the ravine at the bottom. A few walled houses in the distance line the rim of the hill above.

I felt like Dorothy going behind the curtain, when she suddenly confronts the Wizard as he manically pulls levers to present his fierce, disembodied face to the audience out in front. Like the Wizard’s, you can only see Kikito’s visage the right way from the other side of the curtain – in this case, the metal fence separating Tecate from the U.S.

Viewed from the U.S. side, Kikito becomes an enormous black and white toddler, his chubby hands appearing to grip the top of the border-wall as he seems to look over it, into the mysterious United States. He has a slight smile.

If we’d been on the U.S. side, driving east from San Diego, we could have followed the directions Kikito’s creator, the French artist JR, posted on his website. There you can even see JR’s photograph of two U.S. Border Patrol agents staring at the baby. Apparently they often help visitors find the right spot.

We now have 20,000 Border Patrol agents, whose parked vans dot the desert all along the border wall from California to Texas, as they wait to grab someone trying to cross. Helping visitors find Kikito must provide a welcome break in the tedium of watching and waiting, and sweating in vans on shadeless hills, where the temperature climbs to 105 degrees and above.

It’s obvious that Kikito’s audience is located in the United States. “The piece is best viewed from the U.S. side of the border,” JR’s website explains. In fact, the optical effect can only be seen from that side—Mexicans standing in Tecate, where it’s actually located, can’t see it the right way. JR says Kikito is looking “playfully,” but then admits, “Kikito and his family cannot cross the border to see the artwork from the ideal vantage point.”

I took a photo of Laura on a nearby hummock, just to give an idea of the structure’s immense scale. She seems diminutive next to it. In her classes at the Colegio de la Frontera Norte (COLEF) in Tijuana, and in her books and research about the migration of Mexico’s indigenous people to Baja California and eventually to the United States, Laura Velasco is hardly dispassionate. She advocates for migrants, and has no love for the wall and its unsubtle messages of “Keep Out!” and “Stay in Mexico!”

That’s one reason she liked Kikito. “He shows us to be human beings,” she said, looking up at his half smile. “That’s a good message for people in the U.S. And he does it without shouting, just by being who he is.” If people in Mexico can’t see him properly, she thinks, they’re not the ones who need to get the message anyway.